|

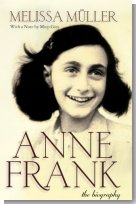

Anne Frank The Biography |

![]()

The Arrest

by Melissa Müller

Translated by Robert and Rita KimberHush. Be quiet. Whisper. Walk softly...take off your shoes. Who's still in the bathroom? The water's running. For God's sake, don't flush the toilet! After two years you should know better than to be so careless. Empty the chamber pots. Shove the beds back out of the way. The church bells are already ringing the half hour. When the workers arrive at 8:30, there has to be dead silence.

The usual morning ritual in the secret annex. At 6:45 the alarm clock goes off in Hermann and Auguste van Pels's room, so loud and shrill that it wakes the Franks and Fritz Pfeffer, who sleep one floor below. The sounds that come next are maddeningly familiar. A well-aimed blow from Mrs. van Pels silences the alarm. The floor creaks, softly at first, then louder. Mr. van Pels gets up, creeps down the steep stairs, and, the first in the bathroom, hurries to finish.

Anne waits in bed until she hears the bathroom door creak again. Her roommate, Fritz Pfeffer, is next. Anne sighs, relieved, enjoying these few precious moments of solitude. With eyes closed, she listens to the birdsong in the backyard and stretches in her bed. Bed is hardly the word for the narrow sofa she has lengthened by putting a chair at one end. But Anne thinks it's luxurious. Miep Gies, who brings the Franks their groceries, has told her that others in hiding are sleeping on the floor in tiny windowless sheds or in damp cellars. Dutifully, Anne gets up and opens the blackout curtains. Discipline rules their lives here. She glances at the world outside. The foggy Friday morning promises to turn into a gloriously warm summer day. If she could just, only for a few minutes... But she must be patient. It won't be much longer now. The attempt to assassinate Hitler two weeks ago has revived everyone's hopes... Perhaps she can go back to school the fall. Her father and Mr. van Pels are sure that everything will be over in October, that they will be free... It is already August. August 4, 1944.

An hour and forty-five minutes is all they have to prepare for another day. An hour and forty-five minutes passes quickly when eight people have to wash up, store their bedding, push the beds aside, and put tables and chairs back where they belong. After work begins at 8:30 in the warehouse below, they can't make a sound. It would be easy to give themselves away. The warehouse foreman, Willem van Maaren, is suspicious enough as it is.

Before a light breakfast at nine, they occupy themselves as quietly as possible, reading or studying, sewing or knitting. And they wait. They must be especially careful during this next half hour. Anyone who absolutely has to get up tiptoes across the room like a thief, in stocking feet or soft slippers, and they have to whisper. If someone laughs or pricks a finger and says "ouch!" everyone glares. But once the office staff has arrived and the rattling typewriters, the ringing telephone, and the voices of Miep Gies, Bep Voskuijl, and Johannes Kleiman -- all friends and helpers of the residents in the secret annex -- form a backdrop of sound, the danger is diminished somewhat. Eventually Miep will come to pick up the "shopping list." In fact, Miep will have to settle for whatever she can get them, and every day she gets a little less. But she knows how eagerly the inhabitants of the secret annex await her. Anne barrages Miep with questions, as she does every morning. And Miep, as she does every morning, puts Anne off until later. Only after Miep has sworn to return for a longer visit in the afternoon will Anne let her go back to her office. Otto Frank retires with Peter van Pels to Peter's tiny room on the top floor. A dictation in English is the lesson plan for today. Peter is having trouble with this irritating language, so Otto spends his mornings helping him. It's a way to pass time. On the floor below, Anne and her sister, Margot, lose themselves in their books. Patience. Patience and discipline -- those are the things that mercurial Anne has had to learn these last two years.

In the warehouse, on the ground floor, the spice mill is running with its familiar monotonous clatter. Van Maaren has the door onto Prinsengracht wide open to let in the light and warmth of this soft summer day.

Ten-thirty. The two warehouse workers have a lot of work to do before the noon break. Suddenly a group of men appears in the shop, one of them in the uniform of the German security service, the Sicherheitsdienst, or SD. The men are armed. A few words are exchanged, then van Maaren -- totally astonished -- points toward the stairs with his thumb. Another worker, Lammert Hartog, stands nervously to one side. The visitors hurry up the stairs to the offices on the second floor. One stays behind to guard the door.

Without knocking, one of the men, short and horribly fat, enters the office shared by Miep, Bep, and Mr. Kleiman. Miep doesn't even look up; people often walk into the office unannounced. Only when she hears his harsh command, "Sit still and not a word out of you!" does she raise her head and find herself staring into the barrel of a pistol. "Don't move from your seat," he orders in Dutch.

Gruff voices can be heard through the double folding doors. The SD man and three of the others, all Dutch, have surprised Victor Kugler at his desk in the next room. "Who owns this building?" the uniformed man bellows at him in German. Kugler, who grew up in Austria, responds in German, "Mr. Piron. We just rent from him." Stiffly erect in his chair, he quickly gives the address of the Dutchman who has owned the building at 263 Prinsengracht since April 1943.

"Stop playing games with me," the SD man snarls. His name is Karl Josef Silberbauer. "Who's the boss here? That's what I want to know."

"I am," Kugler says.

What do these men want? Kugler, a reserved and formal man who strikes many people as utterly unapproachable, tries to collect his thoughts. Have they come after him? Or do they know about the people in the secret annex? Has someone betrayed them? Everything has gone smoothly for two years and a month. Impossible that now, of all times, when the Allies have finally made a breakthrough in northern France and are on the advance, that now, with liberation only weeks away, now, when the tide has finally turned...

A few seconds pass, then his hopes fade. These men know. Denial will only make matters worse.

"You have Jews hidden in this building." Silberbauer's words have the grim sound of a verdict with no possibility of appeal. There is no way out.

Silberbauer is in a hurry; he's on duty. This is merely routine. He orders Kugler to lead the way.

Kugler obeys. What else can he do? The men follow him, their pistols drawn. Kugler's brilliant blue eyes seem -- more than ever -- like an impenetrable wall. But his perfect self-control conceals a feeling of paralyzing helplessness. His mind won't work; his familiar surroundings blur and fade before his eyes. It feels like the final moments before a thunderstorm, muggy, oppressive, threatening. Questions torment him: Who betrayed his charges? A neighbor? An employee? And why today of all days?

Seemingly indifferent, he walks down the corridor that connects the front of the building with the rooms in the rear. One by one he climbs the narrow steps that turn to the right like a circular staircase. The strangers are at his heels. Silberbauer still hasn't gotten used to Amsterdam's terrifyingly steep stairs. Fourteen, fifteen, sixteen. Now they are standing in a hallway whose beige-and-red flowered wallpaper makes it look even narrower than it is. Behind them is the doorway to the spice warehouse, ahead of them a high bookcase: three shelves crammed with worn gray file folders. Above the bookcase hangs a large map of the kind seen in government offices or in schools: Belgium, in 1:500,000 scale.

"Open up." Of course -- they know. A yank on the bookcase and it swings away from the wall like a heavy gate. Behind it, a high step leads to a white door about a foot and a half above the floor; the top of the door is hidden behind the map on the wall. The lintel of the door frame is padded with a cloth stuffed with excelsior: it's easy to bang one's head.

Have the Franks heard the loud footsteps and the unfamiliar voices? When Victor Kugler hesitates, the SD men urge him on. Right in front of them, another stairway, barely wide enough for one person, leads to the upper floor of the secret annex. Kugler goes up the left side of this narrow stairway and opens a door.

The first person he sees is Anne's mother, Edith Frank, sitting at her table. "Gestapo," he says under his breath. His dry lips can't form another word. He is afraid she will panic, but she stays seated, frozen. She looks at Kugler and the intruders impassively, as if from a great distance. "Hands up," one of the Dutchmen barks at her, his pistol in his hand. Mechanically, she raises her arms. Another policeman brings Anne and Margot in from the next room. They are ordered to stand next to their mother with their hands over their heads.

Two of the Dutch policemen have run up the stairs to the next floor. While one of them covers Mr. and Mrs. van Pels with his pistol, the other storms the small room next door. He frisks Otto Frank and Peter van Pels for weapons, as if they were dangerous criminals. Then he herds them into the next room, where Peter's parents wait in silence, staring into space, their hands over their heads. "Downstairs with you, and make it quick." The last to appear, with a pistol at his back, is Fritz Pfeffer.

The SD men seem pleased. Eight Jews at one blow. A good morning's work. "Where is your money? Where are your valuables?" Silberbauer asks, threateningly. "Come on, come on, we don't have all day." The eight captives appear incredibly calm. Only Margot has tears running down her face, but she is silent.

Otto Frank feels that if they cooperate with their captors everything will turn out all right. The Germans are frightened themselves. They know about the Allied offensive, too. They know the end is only weeks away. Otto points to the closet where he keeps his family's valuables. Silberbauer orders his henchmen to search the other rooms and the attic for jewelry and money. He pulls the Franks' bulky strongbox out of the closet. His eyes search the room. He finds what he's looking for: Otto's leather briefcase -- Anne's briefcase, actually, because Otto has given it to his daughter as a safe place to keep her personal papers.

Silberbauer opens the briefcase, turns it upside down, and dumps Anne's diary, notebooks, and loose papers out onto the floor. "Not my diary; if my diary goes I go with it!" Anne had written four months earlier. Now she watches impassively. Silberbauer, irritated by how calm his captives seem, empties the contents of the strongbox into the briefcase and bellows, "Hop to it. You've got five minutes to get ready." As if in a trance, all eight get their emergency packs from the next room or from upstairs, rucksacks that have hung packed and readily accessible in case a fire broke out and they had to abandon the building. They ignore the chaos the Dutch Nazis have created in their search.

SS Oberscharführer Silberbauer can't stand still. In his heavy boots, he paces the small room. People have told him that his marching is intimidating, but it helps him pass the time until everyone is ready to leave. He is thirty-three years old; his pale blond hair is cropped short, in military fashion, over his large, fleshy ears. His lips are pale and thin, his eyes narrowed to slits. An ordinary, rather nondescript fellow: obedient, deferential to authority. It is obviousthat his uniform gives him his place in life. He has the upper hand here, he thinks, and beyond that he does not think. He obeys orders. Clearing out this annex is all in a day's work. Originally a policeman, he joined the SS in 1939. In October 1943, he was transferred from his native city of Vienna to the Amsterdam unit of the Gestapo's Department IV B4, the so-called Jewish Division of the Reich Security Headquarters in Berlin, whose job, under Adolf Eichmann's command, is the efficient "solution of the Jewish question." Silberbauer's wife has remained at home in Vienna.

Suddenly Silberbauer stops his pacing and stares at a large gray trunk on the floor between Edith Frank's bed and the window.

"Whose trunk is that?" Silberbauer asks.

"Mine," Otto answers. "Lieutenant of the Reserves Otto Frank" is clearly stenciled on the lid of the steel-reinforced trunk. "I was a reserve officer in the First World War."

"But..." Karl Silberbauer is obviously uncomfortable. This trunk has no business being here. It upsets his routine. "But why didn't you register as a veteran?" Otto Frank, a Jew, is Silberbauer's superior in military rank.

"You would have been sent to Theresienstadt," he points out, as if the concentration camp at Theresienstadt were a health spa.

His eyes dart nervously around the room, avoiding Otto Frank's.

"How long have you been hiding here?"

"Two years," Otto Frank says, "and one month." When Silberbauer, incredulous, shakes his head, Otto Frank points to the wall on his right. Next to the door to Anne's room, faint pencil marks on the wallpaper record how much Anne and Margot have grown since July 6, 1942. Silberbauer's eyes come to rest on a small map of Normandy tacked to the wall beside the pencil marks. On this map, Otto has kept track of the Allied advance. He has used pins with red, orange, and blue heads, from Edith's sewing basket, to mark Allied victories.

Silberbauer struggles with himself, then says in a choked voice, "Take your time." Is he about to lose his self-control? Has something here touched him? While his assistants guard the captives, he retreats downstairs.

Silberbauer walks through the smaller office, where Victor Kugler was working and where his assistant, Johannes Kleiman, is now being interrogated, then through the windowless hallway, to the large front office. Beyond the windows that reach nearly from floor to ceiling, sunbeams sparkle on the waters of the canal.

Miep Gies has been left alone in the front office. Her husband, Jan, had dropped by, as he did every day at noon, and Miep had secretly slipped him the ration cards she used for the annex residents. Then she had hustled him back out the door. Though Miep's coworker, Bep Voskuljl, could hardly see through her glasses for her tears, Kleiman sent her off to tell his wife what had happened and to give her his wallet for safekeeping. Miep, too, received permission to go, but she chose to stay.

"Well," Silberbauer says to her in German, "now it's your turn." His Viennese accent sounds familiar. Miep was born in Vienna and lived there until she was eleven.

"I'm from Vienna, too," she says in a steady voice.

A fellow Viennese. The Nazi wasn't expecting that. But it's important to stick to routine. Identity card. Standard questions. Silberbauer is in way over his head. "You traitor, aren't you ashamed to have helped this Jewish trash?" he yells at Miep, as if shouting might help him keep the self-control he's on the verge of losing. Since the Allied landing in Normandy, actions against Jews had almost entirely ceased. The SD was preparing for the defense of Holland and had more important things to worry about than the Jews. But the officer in charge of Silberbauer's unit had made an exception; he simply couldn't ignore the tip the unit had received from an anonymous telephone caller. And now Silberbauer has all these complications to deal with.

It requires all Miep's strength to keep calm, but she does, looking Silberbauer straight in the eye. He finally quiets down, mumbles something about feeling sympathy for her, and says he doesn't know what to do with her. Then he leaves, threatening that he will come back the next day to check on her and search the office. He wants to put this assignment behind him and get out of this wretched building.

The truck that has been ordered by phone finally arrives, a delivery truck without windows. Carefully guarded by the Nazi policemen, the eight captives come down the stairs from the annex one by one, walk the corridor past the offices, go down another set of steep stairs, and, finally, outdoors. For the first time in two years and a month, they are on the street. The sunlight blinds them. Inside the truck it is dark again.

Miep remains behind with van Maaren. Lammert Hartog seized the first opportunity to pull on his jacket and disappear. The police have taken Victor Kugler and Johannes Kleiman away with the others. Miep sits at her desk, stunned, exhausted, drained. She could leave now, but she stays. What can she do to help her friends? Is there any way to rescue them? Will the police return?

Minutes pass, or hours -- Miep can't tell. Jan finally comes to find her. Bep comes back, too.

Joined by van Maaren, they make their way into the annex. Silberbauer has locked the door behind the bookcase and taken the key, but Miep has a duplicate. Once inside, they are stunned by the mess the police have left behind. They have pulled everything out of the closets, torn the beds apart. The floor of the Franks' room is covered with notebooks and papers. Among them is a little volume with a checkered cover, like an autograph book. It is Anne's diary. With Bep's help, Miep quickly gathers the papers together. They grab a few books they borrowed from the library for Anne and Margot. Otto's portable typewriter. Anne's combing shawl. But no valuables to keep for their arrested friends. The police have stolen everything of value.

It's late, but outside the sun is still shining, bathing the facade and the interior of 263 Prinsengracht in the clear golden evening light of a Vermeer. Miep collects Anne's diary and the many loose pages without reading a word and puts them in her desk drawer. She doesn't lock it. That would just arouse curiosity. When Anne returns after the war, Miep will give her back her diary.

Copyright © 1998

by Melissa Müller

Translation © 1998 by Metropolitan Books

![]()

Purchase now from Amazon.com

Anne Frank : The Biography by Melissa Muller - The first biography of the vivacious, intelligent Jewish girl with a crooked smile and huge dark eyes who has become the "human face of the Holocaust." Utilizes exclusive interviews with family and friends, previously unavailable correspondence, and documents long kept secret, providing a deeper, richer understanding of Anne and the Nazi era.

Return to The History Place - Selected Books on Hitler's Germany

![]()

The History Place thanks all of our visitors who have purchased books!

See also: The History Place selection of |

![]()

[ The History Place Main Page | American Revolution | Abraham Lincoln | U.S. Civil War | Child Labor in America 1908-1912 | U.S. in World War II in the Pacific | John F. Kennedy Photo History | Vietnam War | The Rise of Adolf Hitler | Triumph of Hitler | Defeat of Hitler | Timeline of World War II in Europe | Holocaust Timeline | Photo of the Week | This Month in History ]

Copyright © 2025 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved

Terms of use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place.