![]()

Introduction and Slide Show Index

|

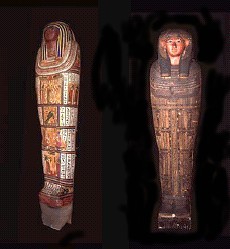

The British Museum of London,

England, has the largest and most comprehensive collection of ancient

Egyptian material outside of Cairo. Its spectacular collection consists

of more than 100,000 objects. Displays include a gallery of monumental

sculpture and the internationally famous collection of mummies and coffins. Egyptian objects have formed part of the collections of the British Museum since its beginning. The original start of the Museum was to provide a home for objects left to the nation by Sir Hans Sloane when he died in 1753, about 150 of which were from Egypt. European interest in Egypt began

to grow in earnest after the invasion of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798, particularly

since Napoleon included scholars in his expedition who recorded a great

deal about the ancient and mysterious country. After the British defeated

the French in 1801, many antiquities which the French had collected were

confiscated by the British Army and presented to the British Museum in

the name of King George III in 1803. The most famous of these was the

Rosetta Stone. After Napoleon, Egypt came under

the control of Mohammed Ali, who was determined to open the country to

foreigners. As a result, European officials residing in Egypt began collecting

antiquities. Britain's consul was Henry Salt, who amassed two collections

which eventually formed an important core of the British Museum collection,

and was supplemented by the purchase of a number of papyri. Antiquities from excavations also came into the Museum in the later 1800's as a result of the work of the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society). A major source of antiquities came from the efforts of E.A. Wallis Budge (Keeper 1886 -1924), who regularly visited Egypt and built up a wide-ranging collection of papyri and funerary material. In May of 2003, the British Museum signed a landmark five-year collaborative agreement with the Bowers Museum of Santa Ana, California, to showcase its incredible collections and to provide a service to visitors and especially students who aren’t able to travel to Britain. In April 2005, the Bowers Museum thus presented "Mummies: Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt" featuring a spectacular collection of 140 objects from the British Museum. For your enjoyment, The History Place presents a slide show highlighting 14 items from the Bowers Museum exhibition. About Egyptian

Mummies Mummies are one of the most characteristic

aspects of ancient Egyptian culture. The preservation of the body was

an essential part of the Egyptian funerary belief and practice. Mummification seems to have its origins in the late Predynastic period (over 3000 BC) when specific parts of the body were wrapped, such as the face and hands. It has been suggested that the process developed to reproduce the desiccating (drying) effects of the hot dry sand on a body buried within it.

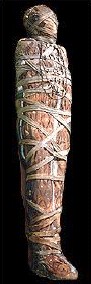

The best literary account of the mummification

process is given by the Ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who says that

the entire process took 70 days. The internal organs, apart from the heart

and kidneys, were removed via a cut in the left side. The organs were

dried and wrapped, and placed in canopic jars, or later replaced inside

the body. The brain was removed, often through the nose, and discarded.

Bags of natron or salt were packed both inside and outside the body, and

left for forty days until all the moisture had been removed. The body

was then cleansed with aromatic oils and resins and wrapped with bandages,

often household linen torn into strips. In recent times, scientific analysis of mummies,

by X-rays, CT scans, endoscopy and other processes has revealed a wealth

of information about how individuals lived and died. It has been possible

to identify medical conditions such as lung cancer, osteoarthritis and

tuberculosis, as well as parasitic disorders such as schistosomiasis (bilharzia). Mummification The earliest ancient Egyptians buried their dead in small pits in the desert. The heat and dryness of the sand dehydrated the bodies quickly, creating lifelike and natural 'mummies' as seen here.

Egyptian Amulets Egyptian amulets (ornamental charms) were worn by both the living and the dead. Some protected the wearer against specific dangers and others endowed him or her with special characteristics, such as strength or fierceness. Amulets were often in the shape of animals, plants, sacred objects, or hieroglyphic symbols. The combination of shape, color and material were important to the effectiveness of an amulet.

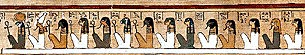

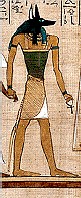

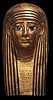

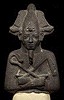

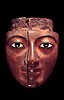

Papyri (Egyptian scrolls) show that amulets were used in medicine, often in conjunction with poultices (a medicated dressing, often applied hot) or other preparations, and the recitation of spells. Sometimes, the papyri on which the spells were written could also act as amulets, and were folded up and worn by the owner. One of the most widely worn protective amulets was the wedjat eye: the restored eye of Horus. It was worn by the living, and often appeared on rings and as an element of necklaces. It was also placed on the body of the deceased during the mummification process to protect the incision through which the internal organs were removed. Several of the spells in the Book of the Dead were intended to be spoken over specific amulets, which were then placed in particular places on the body of the deceased. The scarab (beetle) was an important funerary amulet, associated with rebirth, and the heart scarab amulet prevented the heart from speaking out against the deceased. Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt The ancient Egyptians believed in many different gods and goddesses -- each one with their own role to play in maintaining peace and harmony across the land.

Egyptian

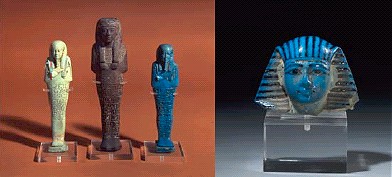

Shabti Figures: Shabti figures developed from the servant figures common in tombs of the Middle Kingdom (about 2040-1782 BC). They were shown as mummified like the deceased, with their own coffin, and were inscribed with a spell to provide food for their master or mistress in the afterlife.

From the New Kingdom (about

1550-1070 BC) onward, the deceased was expected to take part in the maintenance

of the 'Field of Reeds,' where he or she would live for eternity. This

meant undertaking agricultural labor, such as plowing, sowing, and reaping

the crops. The shabti figure became regarded

as a servant figure that would carry out heavy work on behalf of the deceased.

The figures were still mummiform (in the shape of mummies), but now held

agricultural implements such as hoes. They were inscribed with a spell

which made them answer when the deceased was called to work. The name

'shabti' means 'answerer.' From the end of the New Kingdom, anyone who could afford to do so had a workman for every day of the year, complete with an overseer figure for each gang of ten laborers. This gave a total of 401 figures, though many individuals had several sets. These vast collections of figures were often of extremely poor quality, uninscribed and made of mud rather than the faience which had been popular in the New Kingdom.

Begin

The History Place - Slide Show Index of Objects

All images reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. Informational text provided by the British Museum. The History Place Terms of Use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place™ |