![]()

Road to Power

1923 - 1933

Following the failed Beer Hall Putsch and Hitler's arrest, the Nazi Party and Youth League of the NSDAP had been outlawed. Gustav Lenk, former leader of the Nazi Youth League, then founded a new group, the Patriotic Youth Association of Greater Germany. However, German officials soon disbanded this group, believing it was just another name for the Nazi Youth League.

Lenk was arrested and briefly imprisoned, but upon his release, founded yet another group, the Greater German Youth Movement. He was arrested again and sent to Landsberg Prison where Hitler was confined. Lenk wound up being released from prison about the same time as Hitler in December of 1924.

After his release, Hitler announced he would re-found the Nazi Party and invited all German nationalists to join the revitalized Nazi Party with him as its undisputed leader. However, Lenk doubted Hitler could maintain his position as absolute leader. Lenk then founded a new nationalist youth group independent of the NSDAP. The Nazis retaliated by discrediting Lenk via trumped up charges that he was a traitor and petty thief. This resulted in Lenk's downfall and complete removal from the entire German youth movement scene. He was replaced by Kurt Gruber, a 21-year-old law student who had joined the Nazi Party in 1923. Gruber had served as a group leader under Lenk and was a skilled organizer.

Gruber introduced the first Hitler Youth style uniforms featuring a brown shirt and black shorts and a unique arm band with a Nazi swastika minus the white circular background. The arm band included a white horizontal stripe to easily distinguish the young members from brownshirted storm troopers, the SA, who resented being confused with the youths.

Hitler was impressed by Gruber's zeal and organizational talent. The Greater German Youth Movement under Gruber became the official youth organization of the Nazi Party and was even allowed to retain a degree of independence from the NSDAP leadership.

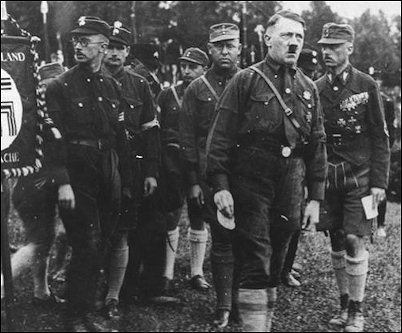

For Hitler, 1925 was a year spent successfully rebuilding the Nazi Party and consolidating his position as absolute leader. Amid this success, Hitler called for his first mass rally since his release from prison. He chose the city of Weimar, located in the German state of Thuringia, which was one of the few states where he could legally speak in public. On July 3rd, 1926, a two-day Nazi rally began and was attended by Gruber's youth group.

On Sunday, July 4th, at the suggestion of Julius Streicher, Gruber's Greater German Youth Movement was renamed as the Hitler Jugend, Bund der Deutschen Arbeiterjugend. Thus the Hitler Jugend (HJ) or Hitler Youth was born. Kurt Gruber was then officially proclaimed as its first leader. All other National Socialist youth associations, including groups in Austria, were now absorbed into the Hitler Youth organization.

Gruber next established various departments and procedures. Among the 14 separate departments were ones for sports, propaganda and education.

New guidelines stipulated: that all Hitler Youth members over age 18 had to be Nazi Party members; appointments to high ranking positions required Party approval; Hitler Youths must obey all commands issued by any Nazi Party leader; pay a membership fee of four Pfennigs per month; and wear standardized uniforms designed to avoid confusion with storm trooper uniforms.

By the end of 1927, a further requirement was that Hitler Youths turning 18 had to join the storm troopers. However, this resulted in a shortage of trained leaders within the upper echelons of the Hitler Youth. The Youth Committee of the NSDAP then worked out an arrangement with the SA allowing valuable members to stay in the Hitler Youth past age 18.

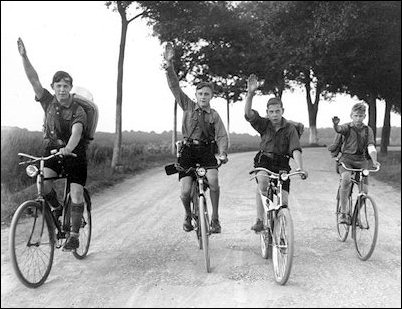

With new branches in twenty different German Gaue (districts), the Hitler Youth organization faced financial problems associated with its expansion. Paid dues and Party funds only covered a portion of the costs. Hitler Youth members then began the practice of collecting money during propaganda marches.

Those marches always included the attention getting, rousing singing of Hitler Youth boys. Their songs, borrowed mainly from the pre-war German youth movement, were based on old ballads and traditional German folklore. They also borrowed tunes from other nationalist groups and other political organizations, even the Communists, and simply changed the lyrics.

First Nuremberg Appearance

At the Nuremberg Party rally in 1927, about 300 Hitler Youth members marched alongside 30,000 brownshirted storm troopers. This was the first appearance of the Hitler Youth at the annual Nuremberg rallies. Adolf Hitler took notice of his young followers and paid special tribute to them. Due to a lack of money, many of the boys had walked all the way to Nuremberg.

In 1928, the Hitler Youth organization continued its slow, steady growth and began making contacts with youth groups outside of Germany, including Sudeten Germans in Czechoslovakia and ethnic Germans living in Poland.

On November 18, Gruber introduced the first Reichsappell, special days of the year in which all Hitler Youth units were required to simultaneously stage public rallies and listen to special orders of the day and Nazi Party proclamations.

At the end of 1928, Gruber called for a meeting of the entire Hitler Youth leadership to streamline the organization. That meeting resulted in the addition of a new department for boys aged 10 to 14, later known as the Jungvolk. A separate branch was established for girls, later called the Bund Deutscher Mädel, the League of German Girls, or BDM. Another new department was the Hitler Youth news service, set up to assist with Nazi propaganda and publish youth oriented newspapers to overcome the "Jewish monopoly of news."

Gruber also reaffirmed the unique identity of the Hitler Youth as "a new youth movement of young social-revolutionary minded Germans" trained to risk their own lives if necessary to free Germany from "the shackles of Capitalists and the enemies of the German race."

Baldur von Schirach Emerges

Although Gruber enjoyed much success, competition for his position soon arose from an ambitious young upstart named Baldur von Schirach. He had joined the Nazi Party at age 18 upon hearing Hitler speak for the very first time. Schirach was the son of a wealthy Prussian army captain and an American mother whose ancestors included two signers of the American Declaration of Independence. Schirach was educated at the best German schools and quickly came to the attention of Hitler after joining the Party.

At Hitler's prompting, Schirach attended the University of Munich to study Germanic folklore and art history. He joined the local Nazi Student Association as well as the storm troopers, although they tended to poke fun at him because of his upper class, schoolboy looks. But young Schirach and his wealthy family enjoyed Hitler's friendship and confidence. Hitler made many social visits to his home.

In July 1928, Schirach was appointed Leader of the Nazi Student Association and was made an adviser for student affairs at Nazi Party headquarters in Munich. The ambitious young Schirach soon set his sights on gaining control of the Hitler Youth organization as well.

Gruber became aware of Schirach's ambitions and made personal appeals to Hitler Youth leaders for their continued loyalty. He also attempted to make a favorable impression on Hitler by expanding the newspaper activities of the Hitler Youth. Two monthly papers were established, Die Junge Front and Hitler Jugend Zeitung, along with a bi-weekly. But the papers never sold well. Gruber later required boys wanting promotions within the Hitler Youth to sell a fixed quota each month in order to qualify.

In April 1929, the Hitler Youth was declared the only official youth group of the Nazi Party. In September, Hitler Youths made a strong showing at the annual Nuremberg rally as about 2,000 members marched past Hitler amid great applause. Among them was a group of Berlin boys who had marched 400 miles all the way to Nuremberg. This became an instant tradition and would be repeated each year, known as the Adolf Hitler March.

The Hitler Youth organization had grown from 80 branches with 700 members in 1926 to about 450 branches with 13,000 members in 1929. But it was still a tiny organization, considering that throughout Germany there were a total of 4.3 million young people involved in a wide variety of youth groups. However, the Hitler Youth movement, like the Nazi Party itself, would soon experience enormous growth as a result of the economic catastrophe brought on by the Great Depression.

Young Political Activists

In Germany, the severe economic hardships of the Great Depression, which began in October 1929, destabilized the democratic government, spurring anti-democratic groups into action including the Nazis and Communists. On March 20, 1930, Hitler Youths gathered in Berlin for their first solo mass rally. It had the theme "From Resistance to Attack" and featured inflammatory speeches by Berlin Gauleiter Joseph Goebbels and Hitler Youth Leader Gruber.

The radical tone of the speeches attracted the attention of local police and public authorities, resulting in a crackdown on the Hitler Youth. Propaganda marches were banned and German schoolboys were prohibited from joining. Penalties included possible expulsion from school and fines. To get around this, local Hitler Youth groups simply renamed themselves with harmless sounding names such as the 'Friends of Nature.' The official crackdown had little overall effect and actually made this 'forbidden' organization more appealing to adventurous teens.

Parents tried in vain to discourage their children from associating with Hitler Youths. The Roman Catholic Church, which had its own extensive youth organization, restricted young parish members from joining. To keep boys from defecting, Catholic youth groups copied some of the practices of the Hitler Youth such as target shooting with small caliber rifles.

Hitler Youth marches, rallies and meetings continued despite the opposition. Political activities of the boys included disrupting the first showing of the anti-war film All Quiet on the Western Front. In the movie, a schoolboy enthusiastically joins the German army in World War I, only to discover the murderous realities of modern warfare. In several German cities and in Vienna, disruptive Hitler Youths inside theaters caused film showings to be cancelled. The film was then taken out of general circulation in Germany.

1930 was a landmark year in the rise of Hitler and the Hitler Youth played an important role. Throughout Germany, along with Nazi storm troopers, they tirelessly campaigned to get Nazis elected to the Reichstag in the now-faltering democratic government. In the election held on September 14, 1930, Nazis received 18 percent of the vote, winning 107 seats in the Reichstag, instantly becoming the second largest political party in Germany.

Gruber's Downfall

Despite the success of the Hitler Youth, Kurt Gruber's position as leader became shaky due to the unceasing behind-the-scenes manipulations of Balder von Schirach and the return of Ernst Röhm from South America to assume command of the SA.

Hitler had recalled Röhm from South America after unrest occurred within the ranks of his storm troopers, including an open revolt in Berlin in March 1931. Following the revolt, Hitler named himself Supreme Commander of the SA, with Röhm as its Chief of Staff actually running the organization.

The Hitler Youth organization under Gruber had been operating as a semi-independent entity within the SA. Under Röhm, that was about to change. In April 1931, at Röhm's request, Hitler issued an order placing Gruber directly subordinate to the SA Chief of Staff. The headquarters of the Hitler Youth organization was also moved from Plauen to the main Nazi headquarters in Munich.

Worse for Gruber, he was criticized by Schirach for the heavy financial losses of the Hitler Youth organization. Newspaper sales and fund raising had been hurt by local government bans on Hitler Youth publications as well as bans on general activities. Schirach capitalized on this and now claimed that he, not Gruber, was the man who could successfully lead a reorganized and revitalized Hitler Youth organization on a national level, and that Gruber had shown a lack of vision and organizational ability. Gruber was also criticized by Röhm over the slow growth of the Hitler Youth compared to the huge increase of memberships in the Nazi Party. Gruber countered the growing criticism by promising Hitler that he would double membership by the end of 1931, a promise that would be nearly impossible to keep.

In October 1931, Nazi Party headquarters in Munich abruptly announced it had accepted Gruber's resignation, although in reality he never actually submitted one. After three years of intense work building the Hitler Youth organization, Gruber was gone, replaced by the 24-year-old Schirach.

About Schirach

Schirach had proven himself an able organizer and propagandist while he was a student leader. Although he was from an upper class background, he became a militant opponent of his own social class. He was also an anti-Semite as well as an opponent of Christianity.

As one of the earliest members of the Nazi Party, he was among Hitler's inner circle and was personally well regarded by Hitler. Schirach was a romantic and a self-styled poet who had worshipful admiration for Hitler. He expressed blind devotion in sentimental writings, describing Hitler as "this genius gazing at the stars" and stating that "loyalty is everything and everything is the love of Adolf Hitler."

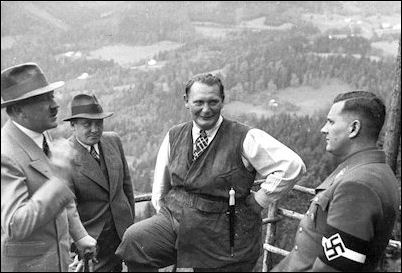

Schirach's flattery was also an effective means of furthering his own advancement. Hitler had a notable weakness for flattery which was well known to members of his inner circle, including Goebbels, Hermann Göring, and Heinrich Himmler. They constantly tried to outdo each other in lavishing praise upon him, but none were better at it than Schirach.

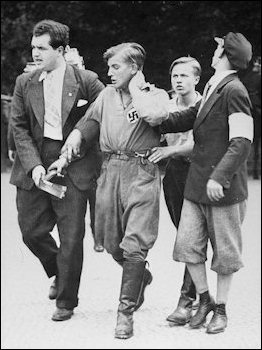

In a directive issued by Hitler on October 30, 1931, Schirach was appointed to the newly created office of Reichsjugendführer (Reich Youth Leader) directly responsible to the Chief of the SA. The Hitler Youth organization, as well as the two Nazi student organizations already led by Schirach, were all combined and placed under Schirach's control. The Nazi student organizations were known for the virulent anti-Semitism of its young members who harassed and sometimes beat up Jewish teachers and administrators as well as anyone expressing anti-Nazi opinions. Immediately after his appointment as Reichsjugendführer, Schirach weeded out any leaders not entirely devoted to Hitler.

Schirach and SA Leader Röhm were allied in internal political squabbles within the Nazi Party and personally got along very well, a relationship that caused malicious gossip. Röhm was a known homosexual and Schirach had a somewhat delicate persona with his upper class schoolboy looks and mannerisms considered effeminate by battle hardened storm troopers. Schirach, like most of the top Nazi leaders, was unable to live up to the Nazi ideal for men – the tough, athletic, young blond.

Although Schirach enjoyed the support of Hitler and strong backing among the Nazi Party leadership, throughout his entire career as Hitler Youth Leader, he would have to overcome persistent gossip and ridicule, struggling to be taken seriously by the brutal minded Nazi youths under his command. One rumor widely circulated was that Schirach's bedroom was 'girlishly' decorated all in white.

Demise of Democracy

In 1932, Hitler Youths, along with the SA, took part in four separate election campaigns – two Reichstag elections and two Presidential elections. Hitler's goal was to achieve power democratically and then eliminate democracy. But the campaigns cost a lot of money and the Nazi Party ran into serious financial difficulties. The Hitler Youth organization essentially went broke. Although it continued to attract more members, new boys mostly came from unemployed families.

During overnight camping trips, the new boys relaxed around the camp fire and learned Nazi slogans while joining in sing-a-longs of Hitler Youth and Nazi anthems. Political instruction took place during weekly Heimabends (home evenings) in the houses of Hitler Youth. The agenda was usually set via special educational letters sent to local Hitler Youth leaders giving detailed instructions on how to conduct the meetings. During these meetings, propaganda activities for the following week were also planned.

To the average German, their elected democratic leaders seemed unable to cope with the enormous daily sufferings brought on by the Great Depression. Throughout Germany, thousands of businesses and banks had failed. People lost their life's savings. Millions were now unemployed, struggling just to put food on the table to feed their children.

As the democratic government in Berlin slowly unraveled under this pressure, the Nazis and other rival political groups, especially the Communists, positioned themselves to seize power. The Communists were the Nazis main rivals and had their own storm trooper organization, the Red Front, whose members were always willing to fight Nazis in the streets. Violent street incidents also erupted between Hitler Youths and young Communists.

Uniformed Hitler Youths, like the brownshirted SA, were a visible force in the streets, campaigning for Hitler and conducting frequent propaganda marches. Street battles between Communist youths and Hitler Youths occurred regularly. They battled with fists and sticks but increasingly resorted to the use of firearms. Between 1931 and 1933, twenty three Hitler Youths were killed in the streets. The best known case involved twelve-year-old Herbert Norkus.

Early on the morning of Sunday, January 26, 1932, he went out with his local Hitler Youth troop posting notices of an upcoming anti-Red meeting. The boys were then attacked by a troop of Communists and scattered, but Norkus was caught and stabbed twice. He ran to a nearby house for help but the owner shut the door in his face. Norkus was then stabbed five more times and left a trail of bloody hand prints along the outside wall of the house as he tried to pull himself up. The incident became the focus of the Nazi feature length propaganda movie Hitler Junge Quex which starred actual members of the Berlin Hitler Youth.

In April 1932, attempting to halt the widespread political violence, the German democratic government banned both the SA and the Hitler Youth. However, for German teenagers, the lure of joining this now-forbidden youth organization resulted in a surge of new recruits. A few months later, due to behind-the-scenes political manipulations by Hitler, the ban on the SA and Hitler Youth was suddenly lifted.

Hitler and the Nazis were now close to achieving power. In the parliamentary elections held on July 31, 1932, the Nazis became the largest political party in Germany, receiving 13.7 million votes granting them 230 seats in the Reichstag. The tireless propaganda activities of the Hitler Youth had helped enormously to achieve this. All over Germany they had handed out millions of pamphlets and special editions of Nazi newspapers and conducted countless propaganda marches.

In October, to celebrate Hitler's success and the growing strength of the Hitler Youth movement, Schirach asked the entire membership to gather for a Reichsjugendtag der NSDAP (Reich Youth Day) rally at Potsdam.

Although there were initial concerns over the number that would actually show up, over 80,000 members travelled on foot, by bus and rail, converging on Potsdam and overwhelming the city. On October 2nd, they staged a parade beginning at 11 a.m. lasting until 6 p.m. A teary-eyed Hitler stood on the reviewing stand saluting them, deeply impressed by their resolve and their overwhelming turnout. The Hitler Youth organization now had about 107,000 members. It would soon number in the millions.

Copyright © 1999 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved

![]()

NEXT SECTION - Prelude to War

The History Place - Hitler Youth Index Page

The History Place Main Page

Terms of use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place.