The Four Chaplains

|

|

|

|

One of the more extraordinary acts of heroism during World War II occurred in the icy waters off Greenland after a U.S. Army transport ship was hit by a German torpedo and began to sink rapidly. When it became apparent there were not enough life jackets, four U.S. Army chaplains each removed theirs, handed them to frightened young soldiers, and chose to go down with the ship.

In February 1943, the U.S. Army transport ship Dorchester was filled to capacity, carrying 751 passengers, 130 crew members and 23 naval personnel on a journey from Newfoundland to an American military base in Greenland. The 5,649-ton ship was built in 1926 and originally served as a luxury coastal liner. And so by 1943, the ship clearly had seen better days and most of the troops had been quite uneasy boarding such a "lousy old freighter."

The Dorchester was one of three transports in a small convoy, accompanied by three U.S. Coast Guard cutters. Seas were rough and the Dorchester rode the waves poorly, dipping and swaying, bouncing and shuddering as it plowed through the blackness of a cold winter's night.

Throughout the voyage, the four chaplains; George L. Fox, Alexander D. Goode, Clark V. Poling and John P. Washington, helped to soothe the nerves of the 700 young draftees and enlisted men on board by walking among them. They laughed, joked and even put on amateur floor shows every night. The chaplains also held regular religious services which at first were poorly attended. However, attendance increased with every mile the ship sailed further away from home.

To reach Greenland, the convoy had to pass through U-boat infested waters where numerous transports already had been sunk. On the evening of February 2nd, one of the Coast Guard cutters detected a submarine on its sonar and blinked the warning "we are being followed" to Dorchester's Captain, Hans J. Danielsen. An urgent radio call then went out requesting anti-submarine patrol planes. But the response came back that the planes were patrolling "elsewhere." The ships would have to go it alone.

By now, they were only about 150 miles from their final destination and hopes were high they might make it to port without trouble. But as a safety precaution, Captain Danielsen ordered all of the men on board to sleep in their regular clothing and wear life jackets. Many of the men deep in the ship's hold ignored this order due to the sweltering engine heat and the uncomfortable bulkiness of the life jackets.

At one o'clock in the morning of February 3rd, the ship's bell struck twice. It would never sound again. The periscope of German submarine U-223 poked through the water's surface and spotted the ship in its cross hairs. A German officer gave the order to fire torpedoes.

The Dorchester was blasted on its starboard side near the engine room, far below the water line, killing a hundred men and knocking out all power and radio contact. Captain Danielsen was then informed his ship was rapidly taking on water. He gave the order to abandon ship.

Panic now set in among the men below decks as they groped around in the darkness, struggling to get topside. Many had no life jackets or clothing. Those who made it up onto the listing deck immediately realized they were about to die in the Arctic air and frigid water. Lifeboats quickly became overcrowded to the point of capsizing. Rafts were tossed into the sea but drifted away before anyone could get into them. Only two lifeboats out of 14 were successfully launched.

Amid the disorder, the four Army chaplains quietly spread out among the soldiers, preaching courage to the frightened, offering prayers to the wounded, and guiding the disoriented.

After most of the survivors had struggled up on deck, the four chaplains opened a storage locker and began handing out life jackets. Soon they ran out.

"Padre," a young soldier hollered, "I've lost my life jacket and I can't swim!"

One of the four chaplains, it is not known which, removed his and said, "Here, take mine. I won't need it. I'm staying." The other three chaplains followed his example.

"It was," an eyewitness later recalled, "the finest thing I have ever seen or hope to see this side of heaven."

Now, just 27 minutes after the torpedo struck, the ship was about to go down. The four chaplains locked arms together and braced against the deck with its heavy starboard list. They prayed, each in the tradition of his own faith, as the water reached their knees. A wave swept over the ship, then another, and another. The Dorchester fought to right herself but failed and plunged into the seething ocean.

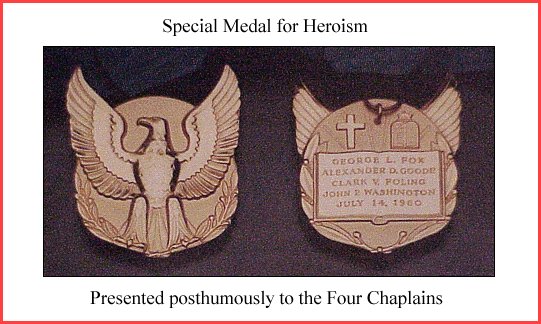

Of the 902 men aboard, 675 died, leaving just 227 survivors. News of the tragedy and the heroic conduct of the four chaplains caused a sensation in America. On December 19, 1944, the Distinguished Service Cross for "extraordinary heroism" and the Purple Heart were awarded posthumously to the chaplains' next of kin. In 1961, Congress authorized a Special Medal for Heroism which had never been given before and is never to be given again.

About the Four Chaplains

George L. Fox (Methodist Minister)

George was the oldest of the four chaplains. Born at the turn of the century in Altoona, Pennsylvania, he was a bright schoolboy who enjoyed reading and was particularly fond of Abraham Lincoln. As a teenager, he developed an interest in religion and began studying the bible on his own. George had an independent streak and did not want to become a farmer like his father.

In 1917, during World War I, he lied about his age and enlisted in the U.S. Marines as a medical corps assistant and was trained to be an ambulance driver. He served on the Western Front in Europe and won a Silver Star for rescuing a wounded soldier from a battlefield filled with poison gas, although he himself had no gas mask. He won the Croix de Guerre for outstanding bravery during an artillery barrage and spent many months in the hospital with a broken back. He also received the Purple Heart.

After the war, George attended Moody Institute in Chicago where he met his future wife, Isadora Hurlbut, from Vermont. They married and had two children. They settled in Vermont where George worked as a public accountant and built a successful practice. One evening, however, George came home from work and told his wife he wanted to study for the ministry. She readily approved.

George then attended Boston University School of Theology and graduated in June 1934. He then served as a pastor at Waits River, Union, and Gilman, in Vermont. He was fondly nicknamed "The Little Minister" because he was only 5 feet 7 inches tall.

George became active in the American Legion veterans' organization and was particularly interested in hospital work and child welfare. Because of his outstanding service, he was appointed Department Chaplain for the State of Vermont for several years.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, George told his wife, "I've got to go. I know from experience what our boys are about to face. They need me." He enlisted in the U.S. Army and attended chaplains' school at Harvard University where he met and befriended Rabbi Alex Goode. George served with the 411th Coast Artillery at Camp Davis, then at Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts, prior to being sent to Camp Taunton in Greenland via the USAT Dorchester.

Before he boarded the Dorchester, he wrote a letter to his little daughter: "I want you to know how proud I am that your marks in school are so high – but always remember that kindness and charity and courtesy are much more important." His daughter received the letter after news had reached that the ship had been torpedoed.

Alexander D. Goode (Jewish Rabbi)

Alex was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Rabbi and Mrs. Goode, the oldest of three boys and one girl. His family moved to Washington, D.C., when Alex was a boy. He was a brilliant student who was always seen with at least one book in his hands. He had particular interest in the United States Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, along with a fondness for mathematics, mechanics and oration.

He attended Eastern High School in Washington, D.C., where he received sports medals for tennis, swimming, and track. After World War I, when the body of the Unknown Soldier was brought to nearby Arlington Cemetery, Alex attended the ceremonies. Rather than take a bus or the family car to the cemetery, Alex chose to walk the entire distance from his home, thirty miles round-trip, as a show of respect.

Alex later joined the National Guard and kept an active membership while training to follow in his father's footsteps and become a rabbi. He married his childhood sweetheart, Theresa Flax. They had a daughter which broke a long string of first-born boys in his family.

Alex became acquainted with one of the leaders of the Reformed Rabbinate, Rabbi Simon, who persuaded him to attend the University of Cincinnati and the Hebrew Union College. Alex received his first rabbinical appointment at Temple Beth Israel in York, Pennsylvania.

Remarkably, Alex said he would know better how to heal men's souls if he knew how to heal their bodies as well. So he decided to pursue a medical degree at John Hopkins University in Baltimore and drove there every day, forty-five miles, while also performing his rabbinical duties.

Alex joined the YMCA and became interested in the interfaith movement. In York, PA, he worked with the superintendent of primary education to form a practical plan of human relations education to eradicate segregation and bias in the York schools. The plan was later adopted for the entire state of Pennsylvania.

Alex paid close attention to the news from Europe concerning Hitler and expansion of the Nazi Reich. He became involved in the American movement to aid Britain. He also tried to enlist in the U.S. Navy as a chaplain, but was turned down due to a lack of vacancies.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Alex applied to the U.S. Army and was accepted. He was sent to the chaplains' training school at Harvard where he met Reverend George Fox.

Alex was assigned to the Army Air Force base in Goldsboro, North Carolina, but was quite unhappy there. He wanted frontline overseas duty to be near the men who needed him most. He pulled many political strings to get sent to Europe. He was first sent to Camp Myles Standish in Taunton, Mass., a port of embarkation. At the camp, he was reunited with Rev. George Fox and also befriended Chaplain Clark Poling and Father John Washington.

One day in 1943, he sent a telegram to his wife: "Having a wonderful experience." Mrs. Goode then knew that Alex had found warm companionship and fellowship among men who could share his faith and his laughter.

Clark V. Poling (Dutch Reformed Church)

Clark was the youngest of the four chaplains. Born in Columbus, Ohio, he had a sister and a brother. While the children were young, the family moved to Auburndale, Massachusetts, where they attended public school. Young Clark was a charming, but mischievous boy, who endeared himself to his teachers.

During World War I, Clark wrote his very first letter in square-block printing. It was received by his father, Rev. Dr. Poling, in a dugout on the Western Front in Europe. "Dear Daddy: Gee, I wish I was where you are. Love, Clark."

The Clark family summered in Marshfield, Massachusetts, at their cottage and enjoyed many good times at the beach. However, illness struck the family and Clark's mother passed away. His sickly father then moved the family to the Poling grandparents in Wilkensburg, Pennsylvania. A year later, the family moved back to Boston. Clark's father then married a widow who had two daughters. They lived in Long Island, New York, before finally settling in Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire.

As a teenager, Clark attended Oakwood, a Quaker school, in Poughkeepsie, NY, where he formed several life-long friendships. After graduation, he attended Hope College in Holland, Michigan, a school of the Dutch Reformed religious tradition. During his second year, Clark decided to become a minister, and would thus become the seventh generation in an unbroken line of ministers in his family.

However, he disagreed with some of his college's policies and decided to leave, finishing his studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Clark then went on to study at Yale Divinity School. After serving student pastorates in Meriden and New London, Conn., he became pastor of the First Reformed Church in Schenectady, NY. He fell in love with and married Betty Jung from Philadelphia. They had a son called 'Corky.' (A little girl was born to Mrs. Poling at Eastertime after the Dorchester went down.)

Following Pearl Harbor, Clark felt he should go off to war but was undecided whether to serve as a soldier or chaplain. "I can carry a gun as well as the next guy," he told his father. "I'm not going to hide behind the Church in some safe office out of the firing line."

"I think you're scared," his father joked. "Don't you know that the mortality rate of chaplains is the highest of all? As a chaplain, you'll have the best chance in the world to be killed. The only difference is, you can't carry a gun to kill anyone yourself."

Clark decided to be a chaplain. He received basic training at Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He served as a chaplain at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and was then sent to Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts prior to being sent on to his next assignment in Greenland.

Clark paid what turned out to be a final visit to his family and congregation at home, before embarking aboard the Dorchester. Alone with his father in Dr. Poling's study, Clark turned to his dad and said: "Dad, Dad, you know how much confidence I have in your prayers, but Dad, I don't want you to pray for my safe return. That wouldn't be fair."

"Many will not return and to ask God for special family favors wouldn't be fair. No, Dad, don't pray for my safe return. Just pray that I shall do my duty, and something more, pray that I shall never be a coward. Pray that I shall have the strength and courage and understanding of men, and especially pray that I shall be patient. Oh Dad, just pray that I shall be adequate."

As a chaplain, Clark taught his men not to bear personal hatred for German and Japanese soldiers or civilians. His instructions were simple: "Hate the system that made your Brother evil. It is the system we must destroy."

John P. Washington (Roman Catholic Priest)

John was born in Newark, New Jersey, the son of poor Irish immigrants. He was the oldest of five boys and two girls. Little Johnny had his father's grin and his mother's stoic determination. He sold newspapers to bring home extra money to help feed the nine mouths in the family. He also loved music and sang in the church choir.

But Johnny was also a mischievous boy. He liked to fight and could be seen occasionally sporting a black eye or bloody nose. One day, while playing with a friend, Johnny suffered a mishap. A BB-gun they were fooling around with accidentally went off and struck Johnny in the eye. It healed but forced the life-long wearing of glasses.

Johnny become an altar boy in the sixth grade and over the next few years began to believe God was calling him to the priesthood. He shared his feelings with his parents and the nuns at parochial school but was careful not to tell anyone else. None of his boyhood friends ever suspected he might want to be a priest due to his ever-present sense of humor and sometimes-salty language. Johnny was even the onetime leader of the South Twelfth Street boys in Newark.

Young Johnny became quite ill at one point and was even given the last rites of the Catholic Church. He recovered and as a result became a much more prayerful and kinder young man.

He attended Seton Hall in Orange, New Jersey, for both high school and college. When he finally broke the news of his intention to become a priest, no one believed him at first. John then attended seminary school at Darlington and was ordained in June 1935. He said his first mass at his old home parish of St. Rose's in Newark.

He was assigned to St. Genevieres in Elizabeth, New Jersey, followed by assignments in St. Venatiaus in Orange, and St. Stephens in Arlington, New Jersey. As a priest, Father John was still one of the boys. He played ball with the kids in the street and also organized parish baseball and football teams along with glee clubs.

After Pearl Harbor, most of the youngsters Father John had known went off to war. Father John wanted to go right along with them. He tried to enlist in the U.S. Navy but was rejected due to his eyesight. He applied to the U.S. Army and was accepted after a long wait. He received basic training at Fort Benjamin Harrison, then received orders for Greenland.

Before he embarked, John felt the need to visit his family and friends to receive their prayers and blessings. The last words he spoke to his mother on leaving: "Goodbye, Ma. No crying, you'll be hearing from me."