![]()

Attack on France

In France, people had shaken their heads in disbelief upon the announcement of a new war with Germany. This would be their third major war against the Germans in the last 70 years. Their grandfathers had fought the war of 1870-71, which the French had lost. Their fathers had fought the First World War from 1914-18. And now this.

The great problem for France was that civilian indifference toward this new war was shared by rank and file soldiers of the French Army.

The French officer corps also had its problems. Senior army leaders had witnessed first-hand the horrific carnage of World War I when men died by the tens of thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands, during battles of attrition at places like Verdun. Haunted by this legacy, they cautiously committed the entire French Army to a defensive posture this time around, thereby passing up the chance to take quick action that could have drastically changed the course of this new war.

ADVERTISEMENT With the German Army entirely preoccupied in Poland, the French had a huge numerical and tactical advantage on Germany’s western border. A hundred well-equipped French divisions stood in place all along the border, while Hitler had just 23 lightly equipped divisions set up as a defensive screen to hold them back. At this point, a French thrust into western Germany targeting the military industries of the Ruhr Valley would have, at the very least, disabled the German war machine by curtailing armaments production, the lifeblood of Hitler's Army.

Instead, the French held their positions, content to rely on a series of newly built steel and concrete fortifications known as the Maginot Line to ward off a potential German invasion. Four British divisions soon joined the French and also stood by on the defensive. Like the French, the British were commanded by cautious generals who had survived the blood-stained battlefields of World War I.

Worse for the French, the country was beset by bitter and disruptive political in-fighting which caused government leaders to become indecisive at a moment of great national peril. Closely watching all of this, Hitler correctly concluded France's political leadership, officer corps, and soldiers, really didn't have the stomach for a fight this time around.

But to knock the French out of the war, Hitler felt he needed to act fast, before the British could fully mobilize and reinvigorate the sagging French. And so, on September 27, 1939, Hitler assembled the Army High Command and ordered his generals to prepare for an invasion of France as soon as possible.

However, there was a problem with this. Hitler's own generals, like their British and French counterparts, now preferred caution. The German Army had just expended nearly all of its available resources to mount the amazing Blitzkrieg attack on Poland and badly needed a few months to regroup, refit and resupply. Right now, German soldiers were simply not ready to leave Poland and abruptly turn westward to fight the French and British. The generals even worried that another drawn-out battle of attrition in France, similar to the First World War, could easily unfold if they rushed into things without adequate preparation.

World War II was barely a month old, but already the seeds of conflict between Hitler and his generals had been sown. Hitler wanted bold action to seize the opportunity of the moment with little regard for the logistics of war or the battle readiness of his frontline soldiers. His generals favored super careful preparation, followed by an attack utilizing overwhelming force to tilt the odds supremely in their favor – just as they had done in Poland.

Now, they needed to stall for time.

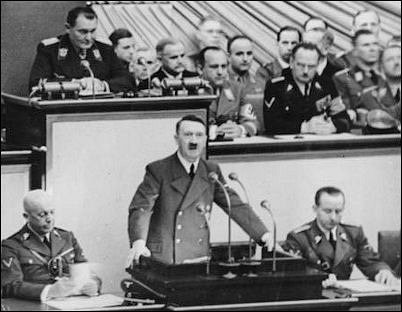

Meanwhile, Hitler the politician ascended the world stage once again, appearing before the Nazi Reichstag on October 6, 1939, to talk peace. Over the past three years, each of his bombastic diplomatic maneuvers or brazen troop movements had been followed by such a speech, offering his own version of events, blaming his victims for their own demise, all the while attempting to placate nervous Germans and manipulate world opinion.

"Germany has no further claims against France," Hitler declared. "I have always expressed to France my desire to bury forever our ancient enmity and bring together these two nations, both of which have such glorious pasts."

To the British, Hitler said, "I have devoted no less effort to the achievement of Anglo-German understanding, no, more than that, of an Anglo-German friendship. At no time and in no place have I ever acted contrary to British interests."

Next, Hitler questioned why anyone would want to fight to save now-defeated Poland. "Why should this war in the West be fought? For the restoration of Poland? The Poland of the Versailles Treaty will never rise again."

To resolve the whole situation, and to address a lengthy list of additional German concerns, including a "solution and settlement of the Jewish problem," Hitler proposed a conference of European leaders.

"And let those who consider war to be the better solution reject my outstretched hand," Hitler added. He then concluded the speech with a warning that if it came to a fight "there will never be another November 1918 in German history," referring to the end of the First World War when the Germans had meekly requested peace terms.

So it seemed, at least to most Germans, that Hitler had offered a genuine peace proposal. All that remained was to wait and see how the British and French would respond.

The next day, French Premiere, Edouard Daladier, informed Hitler that specific guarantees for peace and security would first be needed. The British response came five days later, on October 12th, when Prime Minister Chamberlain addressed the House of Commons. He cited the vagueness of Hitler's proposal, and added there had been no mention of "righting the wrongs done to Czechoslovakia and Poland." Chamberlain also said Hitler needed to demonstrate his desire for peace through acts – not words alone.

Chamberlain's response provided the necessary grist for the Nazi propaganda mill and it swung into high gear, informing the German people that the British wanted war despite the peaceful intentions of the Führer.

Amid all of this trickery, the Army High Command was still trying to stall Hitler. Hoping to persuade the Führer to postpone the attack on France indefinitely, two of its highest ranking generals, Army Commander-in-Chief, Walther von Brauchitsch, and Chief of the General Staff, Franz Halder, met with him on October 7th. They presented solid facts and figures supporting their contention that a major delay was needed.

But the meeting backfired. Three days later, on October 10th, the Führer assembled the entire General Staff. There was to be no discussion. Citing a history of European conflict dating back to the mid-1600s, Hitler lectured them: "The German war aim is the final military dispatch of the West, that is, the destruction of the power and ability of the Western Powers ever again to be able to oppose the state consolidation and further development of the German people in Europe. As far as the outside world is concerned, this eternal aim will have to undergo various propaganda adjustments...This does not alter the war aim. It is and remains the destruction of our Western enemies."

The Führer then issued Directive Number 6 for the Conduct of the War requiring preparations for an attack to "gain as large an area as possible in Holland, Belgium and northern France as a base for conducting a promising air and sea war against England." He set November 12th as the launch date.

Despite Hitler's bombast, Brauchitsch and Halder, and other senior generals, were convinced this attack would be an utter disaster. After trying and failing once more to convince Hitler to wait, they mulled the possibility of taking the ultimate step – the removal of the reckless Führer from power.

It was not the first time they had considered such a move. But the problem now was that the newly expanded Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) had thousands of young officers who had come of age since 1933. Raised during the Hitler era, they had been indoctrinated in Nazism at school, in the Hitler Youth, and by omnipresent propaganda. As true Nazi believers they simply could not be counted on to participate in a widespread military-led anti-Hitler coup. Upon considering this, and amid growing worries about the French and British troop buildup in the West, the generals yielded to caution and decided to do nothing. For the time being, Hitler would get his way.

To prepare for the coming attack, the generals dutifully rushed troops from Poland to the German-French border regardless of their readiness. Soon the number of Wehrmacht troops roughly equaled the number of French and British troops positioned in eastern France along the Maginot Line and along the German-French border including the fortified West Wall, Germany's answer to the Maginot Line.

But when all of the troops were finally in place, nothing happened. Surprisingly, the generals caught a break from Hitler. He issued a weather-related postponement, pushing back the invasion date by three days. Shortly thereafter, he issued a second postponement, pushing the date back another ten days. Fourteen additional postponements followed. Incrementally, and without ever acknowledging their correctness, Hitler was giving his generals the big delay they had wanted.

During this extended lull, the German invasion plan underwent revision after revision. The first versions were eerily similar to the old World War I strategy in which the main invasion force would drive through Belgium into northern France – the same route the Germans had used in August 1914.

But Hitler was dissatisfied with this and urged his generals to think bolder. A daring alternative was then brought to Hitler's attention, concocted by General Erich von Manstein. Why not use the Wehrmacht's armored might to punch through the French lines in the Ardennes Forest, thereby bypassing the Maginot Line entirely, and then roll northward through the countryside to attack the French and British rear, in combination with the big assault through Belgium?

Hitler mulled it over. His senior generals thought it was too risky. But it was precisely that element of risk, even the bit of recklessness involved, that appealed to the Führer. He approved the Manstein Plan and ordered his generals to work out the details.

Meanwhile, frontline Germans stood by idly, staring at their French and British counterparts without firing a shot. The prolonged standoff in the West took on a somewhat comical aspect, jokingly referred to as the Sitzkrieg (sit down war) by the Germans and the Phony War by the British. There was even a touch of optimism in the air as large numbers of troops went home for the Christmas holidays. People began to wonder if there would be a shooting war at all.

The strange lull lasted through the Winter of 1940. However, it was not without consequences for Hitler. Complications soon arose.

First, the British, relying on their naval superiority, had successfully set up a sea blockade that cut off nearly all shipping imports to Germany. A similar blockade had devastated the Germans throughout World War I.

Next, Soviet Russia attacked Finland to steal back the country which been part of the old Russian Empire. The unprovoked attack by Hitler's ally brought British and French promises of ground troops to aid the embattled Finns. The risk for Germany was that those troops, aided by the British Navy, would seize the opportunity to cut off the flow of iron ore from neighboring Norway into Germany, thereby endangering armaments production and the entire war economy.

To prevent this, Hitler chose a drastic measure. He would simply conquer Norway and take Germany's northern neighbor, Denmark, as well. The two neutral countries were militarily weak. The invasions could therefore be limited military operations, relying instead on Nazi ultimatums accompanied by threats of "useless bloodshed."

It began at 5:20 a.m., Tuesday, April 9, 1940, as five highly trained German divisions launched a daring seaborne invasion of Copenhagen, the Danish capital, and Oslo, the Norwegian capital, along with four Norwegian seaports.

In Denmark, things went smoothly. As German troops streamed into the country by sea and land, the Danish King was simply informed his country was now under Hitler’s protection and that resistance was futile. With his small army already overpowered, and to protect his people and cities from Hitler's wrath, Denmark's King Christian and his government surrendered.

In Norway, the Germans had a harder time as the Norwegians refused to submit. Instead, they fended off the initial sea assault at Oslo with cannon blasts from ships and coastal fortifications. As a result, German paratroopers were sent in to capture the city. Norway's King Haakon then delivered a radio message imploring fellow Norwegians to continue resisting and escaped with his government into the northern mountains.

To aid the besieged Norwegians, the British Navy sailed in and blasted away at German warships wherever they were found, sinking ten destroyers at Narvik. Next, British ground troops landed near Trondheim and Hamar. But the outnumbered and ill-equipped British were unable to hold on against German tanks and Luftwaffe attack planes using nearby captured airfields. The British troops were then hastily evacuated from the country along with King Haakon who went into exile in London.

Against all odds, the Norwegians had held out over a month. When it was over, Nazi sympathizer, Vidkun Quisling, a Norwegian who had openly worked to topple his own country for Hitler, became the new head of government.

And so two more countries were swallowed up by Nazi Germany. Hitler regained the momentum in Europe and had bested the British for the moment. The iron ore shipments from Norway would continue and the German Navy and Luftwaffe could use new bases in both Norway and Denmark to confront the British.

With this matter settled, now at long last, Hitler turned his full attention to France, setting a final invasion date of Friday, May 10, 1940.

On that day, the battle began precisely as the British and French had anticipated, with the German invasion of France’s northern neighbors, Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg. Reacting to this, the bulk of the Allied forces, including 136 divisions of French, British and Belgian troops rushed into position, ready to confront the invaders just as they had done in August 1914.

They didn't know they had been hoodwinked. Toward the south, the Manstein Plan was already in motion. A German armored column, stretching back a hundred miles, ripped through the lightly defended Ardennes Forest then roared northward through France toward the English Channel looking to trap the Allied armies. Along the way, French morale crumbled as motorized infantry and Panzer tank corps, commanded by the likes of Heinz Guderian and Erwin Rommel, smashed through the defenders.

At the same time, the Germans crushed Holland. To break the Dutch will to resist, Göring's Luftwaffe struck beautiful Rotterdam, dropping 98 tons of high explosives that destroyed much of the old city. As the Dutch armed forces caved in, Queen Wilhelmina and her government were evacuated to London by the British Navy.

By Monday, May 20, just ten days into the invasion, the entire British Expeditionary Force and three French armies had been cut off in Belgium with their backs to the sea. German armored units then tightened the noose, squeezing the bewildered Allies into a small pocket around the seaport of Dunkirk.

But then they stopped.

In one of the stranger twists of World War II, Hitler's armored units, seemingly on the verge of a stunning victory, suddenly halted their advance on Dunkirk on the morning of May 24th. The chief reason was that Hermann Göring now wanted to grab a share of the spotlight and impress Hitler. He boasted that his Luftwaffe alone could destroy the trapped troops.

Josef Schmid, a Luftwaffe intelligence officer, recalled how it unfolded: “I heard the telephone conversation…Göring described the situation at Dunkirk in such a way as to suggest there was no alternative but to destroy by an attack from the air…and pointed out that the advance elements of the German Army, already battle weary, could hardly expect to succeed in preventing the British withdrawal. He even requested that the German tanks, which had reached the outskirts of the city, be withdrawn a few miles in order to leave the field free for the Luftwaffe."

Hitler agreed to Göring's proposal. German field commanders within sight of Dunkirk were aghast. They could hardly believe their orders.

The British could hardly believe their luck. They immediately prepared for a mass evacuation by sea. The British Navy, aided by a volunteer flotilla of nearly 900 small merchant ships, fishing vessels and pleasure boats of all sizes, sailed across the English Channel to Dunkirk as British soldiers waited for rescue on the beach. One British officer remembered, “Our only thoughts now were to get on a boat. Along the entire queue not a word was spoken. The men just stood there silently staring into the darkness, praying that a boat would soon appear, and fearing that it would not.”

Meanwhile, Göring’s planes were hampered by cloudy weather and then struck by British pilots flying their new Spitfires, the world's finest fighter plane, which could easily shoot down slow-moving German bombers and outmaneuver the Messerschmitt fighters protecting them. This bought time for the troops waiting on the beach and at Dunkirk harbor. It also gave the Allies a last minute chance to regroup. They quickly set up a defensive perimeter around Dunkirk to shield the evacuation from ground attack.

After a two-day wait, realizing that Göring couldn't live up to his boast so easily, Hitler ordered his armored columns to move on Dunkirk. But now they found it hard going in many spots, compared to the rout they might have had. They finally rolled into Dunkirk on June 4th, taking thousands of French prisoners. By this time, however, nearly the entire British Expeditionary Force, about 260,000 men, along with 60,000 Frenchmen, had escaped by sea, knowing that someday, somewhere, they would fight Hitler again.

With Dunkirk, northern France, Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg securely in hand, the entire German Army abruptly wheeled itself around and sped southward to seek out and destroy whatever was left of the French Army.

By now that army was on the verge of collapse. Demoralized, indifferent soldiers were led by indecisive generals paralyzed by the specter of Hitler's earth-shattering Blitzkrieg. A French observer, who spent an hour watching a senior French commander at his headquarters, recalled: “During all that time, he sat in tragic immobility, saying nothing, doing nothing, but just gazing at the map spread on the table between us, as though hoping to find on it the decision which he was incapable of taking.”

The French government itself was in a state of panic. On June 10th, it fled Paris, declaring the capital an open city to hopefully spare its destruction by Hitler.

With ten armored divisions now freely rolling around France, the German Army was presently twice the size of the scattered French Army. On June 14th, German troops drove unhindered into Paris and hoisted the swastika flag of Nazi Germany on the symbol of France, the Eiffel Tower. Three days later, acknowledging the hopelessness of their situation, the French meekly asked Hitler for armistice terms.

For the Germans and for Hitler personally it was a victory almost beyond belief. The German people nearly went mad with joy upon the announcement, realizing there would be no repeat of the First World War in France and Belgium, and believing this new war was, by all appearances, just about won.

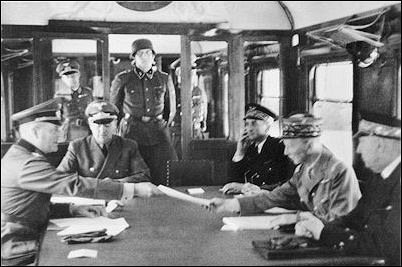

Hitler savored every moment, knowing how his people felt about him. He decided to personally attend the French surrender ceremony, forcing them to sign the document inside the identical railroad car and on the exact spot in the Compiegne Forest where the Germans had surrendered to France two decades earlier, concluding the First World War.

American journalist William Shirer was there that sunny Friday afternoon, June 21, 1940, and watched Hitler's face. "It was grave, solemn, yet brimming with revenge. There was also in it, as in his springy step, a note of the triumphant conqueror, the defier of the world."

Surrender terms required the French to hand over all anti-Nazi refugees along with the entire French navy. To encourage French cooperation, Hitler left mostly rural southern France unoccupied, for the time being, and allowed its day-to-day administration to be handled by a collaborationist regime headed by French Marshal Henri Pétain of World War I fame.

With the conquest of France, nine countries had now fallen to Hitler including Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Holland. Two countries, Spain and Italy, had forged political alliances with Hitler. Only Great Britain remained free among the major European powers.

Once again, Hitler decided to reach out and offer the British an easy way out – peace on his terms.

But Britain had changed. Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister Hitler had bullied at Munich, was gone. In his place as Britain's new leader was a man Hitler had never met, but already didn't like, an avowed anti-Nazi named Winston Churchill.

Copyright © 2010 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved

![]()

NEXT SECTION - Britain Stands Alone

The Defeat of Hitler Index

The History Place Main Index Page

Terms of use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place.