![]()

Defeat in the Desert

Since the beginning of the war, the British had repeatedly landed ground troops in Europe only to hastily withdraw each time, while on the verge of a humiliating rout by Hitler's armies. For Britain's fiery leader, Winston Churchill, this all had to end. The British people and their Army needed a victory on land, somewhere, somehow, and they needed it now.

The opportunity to grab such a victory came in North Africa where troops of Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, were trying to create an African empire for their ambitious leader who was determined, above all, not to be overshadowed by Hitler. Thus far, Mussolini had taken over two countries, Abyssinia and Libya, where his troops had easily rolled over the mostly defenseless inhabitants.

Mussolini set his sights next on Egypt. With a half-million Italian troops at the ready, the only thing standing in his way was a small British force of 36,000 men, comprising the Western Desert Force, based in northern Egypt.

The Italian quest for empire resumed on Friday, September 13, 1940. Outlying British troops in Egypt quickly fell back in the face of overwhelming numbers. But rather than press their advantage, the Italians unwisely paused about 60 miles inside Egypt and set up a series of fortified base camps widely separated from each other. Sharp-eyed British commanders caught this tactical mistake and struck back, targeting the isolated base camps one-by-one, surprising the Italians at each turn and routing them. The British troops, greatly strengthened via the use of captured Italian tanks and artillery, turned their counter-attack into a sweeping offensive lasting for weeks. Two hundred thousand Italians surrendered as the British pushed westward into North Africa, seizing an area bigger than France. It was a stunning victory, just what Churchill had wanted.

But it wouldn't last.

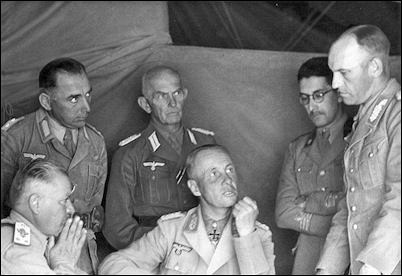

The amazing British success aroused Hitler's attention and he decided to come to the aid of his floundering Italian ally, mindful that a British presence in North Africa brought the distinct threat of Allied entry into southern Europe. And so in February 1941, Hitler sent Blitzkrieg genius, General Erwin Rommel, to direct the newly formed Afrika Korps, featuring two armored divisions and a motorized infantry division.

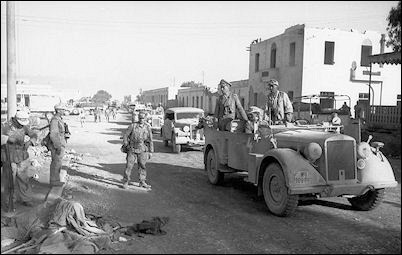

Rommel took to his new post with vigor, relishing the wide open expanses to wage desert Blitzkrieg against the British. Beginning on March 31, his Afrika Korps attacked and within twelve days had pushed the British 500 miles eastward, all the way back into Egypt, while taking thousands of prisoners.

But the British did manage to hang onto one key position outside of Egypt, the port of Tobruk on the Mediterranean Sea, a hundred miles from their lines. At this point, Rommel badly needed that seaport to continue his advance into Egypt, as his own supply lines now stretched 600 miles, all the way back to Tripoli. He called in the Luftwaffe to pound the troops inside Tobruk via heavy bombing raids. However, the British and Australian troops inside the city bravely withstood the bombardment. In the meantime, the Royal Navy sailed in relief troops, including Indian, South African, and Polish replacements. As a result, Tobruk held out. And for the moment, Rommel had to cool his heels and settle for a stalemate.

Churchill, for his part, was unwilling to settle for stalemate. By now, his Western Desert Force had been transformed into the new British Eighth Army, and Churchill pressured its commanders to produce a victory one way or another. As a result, Eighth Army launched a big offensive against Rommel all along the Egyptian Front beginning on November 18, 1941. Although the British lost 300 tanks at the onset, Rommel's tanks ran low on fuel, forcing him to disengage and withdraw westward. By Christmas, Eighth Army had pushed Rommel back the 500 miles he had originally come.

But Rommel was not about to take this lying down. After pausing to regroup and resupply, his Afrika Korps counter-attacked, beginning in January of 1942, pushing Eighth Army back to the outskirts of Tobruk. After this a second stalemate developed and both sides dug in and prepared themselves for the next round in this back-and-forth desert fight.

It came on May 26, 1942, as the Afrika Korps, aided by fresh Italian troops, staged a classic Blitzkrieg attack, surging through the British defenses, finally taking the city of Tobruk, and causing yet another hasty British retreat. The battered British wound up at the village of El Alamein in northern Egypt, only 65 miles from the ancient city of Alexandria. Once again, so it seemed, the British stood on the verge of a humiliating rout – a defeat that could bring Hitler control of the entire Middle East.

But there was a hitch.

To finish off the British and seal the victory, Rommel needed significant troop reinforcements and supplies. When his Afrika Korps arrived on the outskirts of El Alamein poised to strike the British, Rommel had just 125 operational tanks.

Incredibly, Hitler denied Rommel’s request, opting to keep all available resources for the coming spring offensive in Russia. Hitler was now obsessed with achieving victory over Stalin and therefore brushed aside the strategic importance of Egypt. As a result, Rommel’s weakened Afrika Korps was forced to hold its position on the outskirts of El Alamein, thereby giving the British a breather.

Just as they had done at Dunkirk, the British were quick to capitalize on Hitler’s tactical blunder. But this time, instead of leaving, they did the opposite, rushing in soldiers, tanks, artillery and ammunition to support the troops at El Alamein.

In his personal war journal, Rommel himself noted: “When one comes to consider that supplies and materiel are the decisive factor in modern warfare, it was already becoming clear that a catastrophe was looming on the distant horizon for my army. The British were doing all they possibly could to gain control of the situation. With wondrous speed, they organized the shipment of fresh troops into the Alamein position...Our one and only chance to overrun the remains of the British Eighth Army and occupy the east Egyptian desert at a stroke was irretrievably lost.”

Despite the unfavorable odds, however, the ever-aggressive Rommel was not prepared to passively wait for the attack. At the end of August, he tried to seize the momentum and attacked El Alamein utilizing his limited resources. But now he was confronted by a well-equipped Eighth Army outnumbering him two-to-one, and led by a brash new commander, General Bernard Law Montgomery. The attack stalled.

About this time, Rommel needed to leave North Africa. After a year and a half of blazing desert warfare, he was completely worn out physically, and so he went back home to Germany to restore his health.

Meanwhile, Montgomery launched an all-out offensive that would become known as the Battle of El Alamein. It began on Friday, October 23, 1942, with a massive nighttime artillery barrage from a thousand guns that demolished the German outer defenses. This was followed by an advance of British infantrymen across a narrow stretch of German minefields. In Rommel's absence, German field commanders reacted cautiously by sending in infantry, instead of tanks, to block the British and the two sides engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting with heavy casualties.

Rommel rushed back from Germany and immediately threw his 200 remaining Panzers into a ferocious counter-attack. Montgomery reacted by sending in the bulk of his armor, including nearly 800 brand new Sherman tanks, recently delivered from America. In the biggest tank battle of the desert war thus far, Montgomery got the upper hand and broke though the center of the German lines on November 2nd.

Rommel knew the time had come for a strategic withdrawal, but Hitler ordered him to stand his ground regardless. Thus the chance to fall back and properly regroup was missed, resulting in unnecessary loses for the Afrika Korps. Montgomery's tanks smashed through Rommel's weakened defenses, then pushed the decimated Afrika Korps, and its 20 remaining tanks, into a headlong westward retreat, which eventually stretched back over 700 miles.

In Great Britain, church bells were rung to celebrate the breathtaking victory.

For Rommel, things only got worse. On Sunday, November 8, 1942, a large naval armada brought the first contingent of American combat troops into the war amid Operation Torch, led by General Dwight D. Eisenhower. They landed to the rear of Rommel on the beaches of Morocco and Algeria which were then French-controlled colonies in Northwest Africa. French troops defending the area, marginally loyal to their collaborationist government back in Paris, briefly resisted then caved in and began cooperating with the Americans.

The unexpected American landings astounded Hitler and his military staff. They had thought for sure that America would be entirely preoccupied with the Japanese war in the South Pacific.

To prevent the Allies from sweeping to victory in North Africa, Hitler rushed in reinforcements, mainly to halt the American advance at Tunisia. There the very first shots were exchanged between German and American troops in World War II. To the delight of Hitler and his command staff, the Germans got the upper hand in that first engagement at Kasserine Pass, confirming their low opinion of American troops. But the inexperienced Americans, subsequently led by General George S. Patton, recovered from their initial stumble and pressed forward alongside the battle-hardened Eighth Army.

For Rommel's troops, it was all too little, too late. British and American warships and fighter squadrons now dominated the Mediterranean by sheer weight of numbers and promptly isolated the Afrika Korps by completely severing its supply lines. Desperately low on ammunition, fuel and food, the entire Afrika Korps and all of the newly arrived reinforcements, totaling 248,000 men, surrendered to the British and Americans.

Rommel himself had left the area on sick leave once more and therefore was not captured. But he never forgave Hitler for the loss of his beloved Afrika Korps – and would later join an anti-Hitler conspiracy.

For the Allies, victory in North Africa was an important milestone, marking the first time Hitler’s troops had ever been ousted from a region they had controlled. A southern front in Europe against Hitler was only a matter of time.

In Great Britain, Winston Churchill declared: “This is not the end, no it is not even the beginning of the end, but it is perhaps the end of the beginning.”

To his command staff, Hitler acknowledged the loss of North Africa as a setback, but said their primary objective still remained the defeat of Soviet Russia, which would surely bring total victory in the war. To achieve this, Hitler had plunged his armies into a gigantic offensive to capture the city that bore the name of Russia’s leader, a place that would forevermore symbolize the beginning of Nazi Germany’s downfall – Stalingrad.Copyright © 2010 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved

![]()

NEXT SECTION - Catastrophe at Stalingrad

The Defeat of Hitler Index

The History Place Main Index Page

Terms of use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place.