The Patriot

by Karen Feldscher

![]()

In his family’s small house in Fukuoka, Japan, the young boy could hear his father’s hushed conversations with visiting strangers. They would talk about camps.

After the visitors left, the boy would ask his parents: What camps were those? Boy Scout camps? Summer camps?

His mother wouldn’t discuss it. “It’s all in the past,” she’d say. His father stayed silent, too. But as the boy got older, his father told him everything.

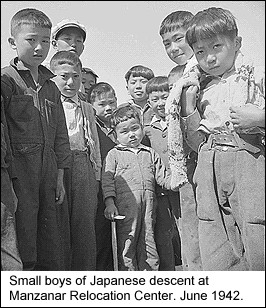

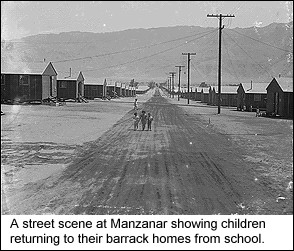

During World War II, a few months after the Pearl Harbor attack, tens of thousands of people living along the U.S. West Coast—two-thirds of them American citizens—were given just seventy-two hours to get their affairs in order, to either abandon their property or sell it for far less than it was worth. Then, their bank assets frozen, allowed to bring only what they could carry, they were transported by bus, truck, or railway cattle car to one of ten “relocation camps” scattered throughout the western states. The boy’s family, living on Terminal Island, in California’s Los Angeles County, was among those rounded up.

For the next three and a half years, men, women, and children, the very old to the very young, were prisoners at the hands of their own country, not because they’d committed any crime, but because they were Japanese.

And so Junro Edgar Wakayama, Ed, to his family and friends—learned about America’s decision to imprison 120,000 of its residents in the name of national security.

The internment was a violation of civil rights; it was racist and, as some officials tried to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the time, unnecessary. It didn’t matter. The entire country was awash with a flood of anti-Japanese sentiment, and many in the government feared Japanese Americans might engage in spying and sabotage.

After the war was over and the camps were closed, Ed’s father, Kinzo, moved his family to Japan. He’d been forced to renounce his American citizenship. Yet Ed says his father bore no grudge against the United States for turning his family’s life upside down.

Neither does the younger Wakayama, born in 1943 in a California internment camp. Unlike his father, Ed Wakayama was able to retain his citizenship and live the American dream. He became a decorated U.S. Army

colonel, now retired, as well as a leading professor and researcher in clinical laboratory sciences. He and his wife, June, have raised two daughters, Lisa, thirty-two, and Liane, twenty-three.

“If anyone has a right to be bitter, it’s him,” says test pilot Tom Carter, who worked with Wakayama at the Pentagon several years ago. “But he’s anything but that.”

Wakayama calls himself a true fan of American-style democracy. Yet he is well aware that democracies can make terrible mistakes. Avoiding them, he believes, requires speaking up. It’s why he regularly travels to colleges and high schools, to talk about the treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II, so young people understand how a government can err so dramatically.

And he warns against a new peril, the USA Patriot Act, which he says is once again curtailing Americans’ basic constitutional rights. “We’re repeating ourselves,” he says plainly. “It’s the same thing as sixty years ago.”

Like a bad spy novel

Wakayama first realized the importance of telling people about the Japanese internment when he was eighteen and back in the United States for the first time since he was a toddler.

Living in Pembroke, Massachusetts, with an aunt and uncle, preparing to begin his studies at Northeastern University in Boston, Wakayama was asked by a local Grange group to give a lecture on Japanese culture. A woman in the audience wanted to know where he’d been born. Manzanar, California, he said—near Death Valley.

Why did his family live there? she asked. He explained: Manzanar was a relocation camp.

“And she said, ‘Excuse me? What do you mean, relocation camp? Is that like a concentration camp?’” Wakayama recalls today. “I said yes. And she said, ‘Oh, there’s no such thing in the United States.’”

He was immediately invited to the next meeting—this time, to talk about the camps. “They were just flabbergasted,” Wakayama says. “They couldn’t believe a thing like that had happened. The lady said, ‘This is horrible. We don’t know our own history.’ That really triggered it for me.”

Now Wakayama’s presentations are anything but off-the-cuff. He’s got PowerPoint graphics. Facts and figures. Family photos. And plenty of passion. Speaking to a Northeastern audience last October, he began by saying, “The story I’m going to tell you is like a page from a bad spy novel. Except it really happened.”

He added, “Many Americans think the internment of the Japanese Americans was caused by the attack on Pearl Harbor. But I’m going to tell you, that’s not the case. The racial prejudice against Japanese Americans started a hundred years before Pearl Harbor.”

If Japanese Americans were such a security threat, Wakayama asks his audiences, why were only West Coast residents put into camps, while another 60,000 Japanese Americans in Hawaii—the site of the Pearl Harbor attack—were left alone? The United States was also at war with Germany and Italy; why weren’t German Americans and Italian Americans imprisoned, too?

The answer is simple, Wakayama says. Internment was about two things: money and prejudice.

Waves of Japanese immigrants had come into the United States during the early part of the twentieth century. Many who settled along the West Coast became prosperous farmers. The success of these “outsiders” aroused their neighbors’ envy and vindictiveness, which led in turn to formal discrimination.

Laws were passed banning Japanese children from “white” schools. The 1924 Asian Exclusion Act prohibited Japanese nationals from becoming citizens. By 1930, more than 600 anti-Japanese statutes had been enacted in the United States. Such laws recalled late-nineteenth-century restrictions against the Chinese, when that group’s gold-mining successes evoked similar prejudice and discrimination.

Pearl Harbor just provided the final straw, Wakayama says. “By early 1942, there was a demand for the incarceration of Japanese Americans by public officials, civic organizations, and especially the Hearst newspapers,” he says. “They called the Japanese ‘the yellow peril.’ War became the perfect pretense to inflame the anti-Japanese feeling that had been brewing on the West Coast.”

Documents show several top advisers told President Roosevelt that interning Japanese Americans was unconstitutional—and that the government didn’t need to do it. Their advice was kept secret. Roosevelt ordered the internment anyway.

A closed-in life

Life in Manzanar was uncomfortable, cramped, dull. Internees lived in military-style barracks, three families to a room, with only curtains for partitions. “Privacy was a major problem,” says Wakayama. “I remember when I was a kid, out of the blue sky, I asked my parents, ‘How did people make love?’ And my dad said, ‘Very quietly.’”

Dust flew through the cracks in the wooden walls. When Wakayama was a small baby, his family stuffed towels in the holes to try to keep the dirt away from him.

In the early going, the camps had no schools; even after Quaker and Mormon groups sent teachers, the children were mostly bored. Many teenagers were angry, blaming their parents for the internment. Food supplies were a problem; wartime rationing meant the prisoners’ food was often stolen for resale on the black market.

“Some people gave up hope,” says Wakayama. “It was really devastating.”

Life for the Wakayama family was particularly tough, because Kinzo Wakayama seldom took a passive approach to injustices.

After the Pearl Harbor attack but before the internment, the elder Wakayama—a U.S.-born attorney who became the first Japanese American secretary/treasurer of the Western Fishermen’s Union—foresaw trouble ahead. He set out to convince government officials that Japanese fishermen living in the western United States would be willing to donate their vessels for war purposes.

Once the internment had been ordered, Kinzo tried another tack: He wrote to officials requesting that Japanese American veterans of World War I, like himself, be exempt. That plea, too, was ignored.

He even considered making a legal protest to what he considered an unconstitutional action. But when armed sailors came to take him and his family away, he surrendered without struggle.

Still, even as a prisoner, Kinzo was seen by authorities as a troublemaker. At the family’s first stop—a makeshift camp at the Santa Anita Racetrack, where they slept on hay in a stall—he criticized the use of internee labor to convert fishing net into camouflage, saying the Geneva Convention forbade forcing prisoners of war to aid in a war effort. That protest landed him briefly in a local jail.

At Manzanar, Kinzo was jailed twice more. Once, for translating camp policy, dining schedules, and work-program information into Japanese for first- generation immigrants who couldn’t understand English: War Relocation Authority policy forbade the use of Japanese at public meetings. Then, for complaining about the diversion of prisoners’ food to the black market. Each time, fellow internees protested by rioting outside the camp’s administration building; each time, unarmed prisoners were injured or killed when guards fired their machine guns into the crowd.

Kinzo was in jail when his wife, Toki, gave birth to Ed, the first of their three sons. In fact, the baby’s middle name was chosen in honor of Edgar Camp, an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer who tried to help the Wakayamas by filing a writ of habeas corpus that challenged the constitutionality of interning U.S. citizens without charges or due process of law. (Kinzo eventually dropped the suit, worn down by camp authorities’ harassment.)

The elder Wakayama’s outspokenness meant the family was shunted from place to place. After Manzanar, they lived in Tule Lake, California (where Ed’s brother Carl was born), then in New Mexico, then Texas. Kinzo was forced at gunpoint to sign away his citizenship. Beneath his signature, he wrote “under duress.”

When the camps closed in 1946, the Wakayama family left for Japan. Things got worse before they got better. The Wakayamas had planned to reconnect with Kinzo’s parents and other family members in Hiroshima. After they arrived in Japan, they learned their relatives had been killed by the atomic bomb. It was too much. Ed Wakayama says his father became so depressed, he at one point considered killing himself and his family.

“But he looked at the boys,” says Wakayama, “and he couldn’t do it.” Eventually, the family settled near Toki’s relatives in Fukuoka, in the south of Japan. A third son, George, was born there.

Back to America

When Wakayama turned eighteen, during the Vietnam War, he was drafted by the U.S. Army. He couldn’t believe his father wanted him to return and serve.

He recalls, “My father said, ‘You’re not a Japanese citizen. If you don’t serve in the Army, you’re a man without a country.’ But I said, ‘Dad, they treated you so bad!’ He said, ‘I assure you, times have changed.’”

And, in truth, Wakayama’s life as a young man in America would be wholly different from his father’s.

His first days back in the United States seemed magical. A May snowstorm in New England diverted his Los AngelestoBoston flight to New York City. From there, he took the train to Boston, gazing out in wonder at the snow-covered countryside. He spent the night at a hotel, waiting for his aunt and uncle to pick him up.

“I didn’t mind waiting,” he says, laughing. “Everything was a new experience. And the people were so nice. I thought, These are the Americans that the Japanese fought? How stupid!”

Wakayama deferred his military obligation by opting to attend Northeastern University and join ROTC. His freshman year was rough. At orientation, President Asa Knowles told the entering class: “Look at the person in front of you, the person in back of you, the person on your left, and the person on your right. Only one will graduate.”

That was enough to throw Wakayama into a tailspin. “I almost fainted, you know?” he admits. “I thought, Oh, no, I’m going to be one of those victims. But I was determined to survive and graduate.” He adds, “Just to be accepted to Northeastern was a miracle for me. If I were to apply today, I wouldn’t have gotten in.”

At first, academics were a challenge. Though Wakayama had taken English classes over the summer, he was still learning the language. “I had a hard time taking notes,” he says. “So I would read the books. If the professor said something outside of the book, I was stuck.

“In English 101, we had to read John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath,” Wakayama remembers. “With some of the Oklahoma slang, I just had no idea what they were talking about. I’d say to my professor, Steve Fine, ‘What does this mean?’ And he’d say, ‘Ed, that’s slang. I don’t blame you for not understanding it!’ He was very accommodating.”

Wakayama also took French to fulfill his language requirement. “I was struggling with English, and French was really tough,” he recalls.

Over time, school got easier. He excelled in science and math. In his sophomore year, he moved in with some new Northeastern friends—all fellow biology majors—and they studied together. “I was very lucky to have these roommates,” he says. “It was cheaper, too. And fun.”

Wakayama found he loved research. While still an undergraduate, he published two papers and received two research awards. After graduating with a bachelor’s in biology and medical technology, he entered the U.S. Army in January 1968 as a clinical laboratory officer at the Fort Ord hospital, in Monterey, California.

“Essentially, I was running a lab,” says Wakayama. “Typical military stuff—here I was a young kid, coming in as a boss for people much more experienced than me.”

Discharged from active duty two years later, Wakayama maintained his Army Reserve status while taking advantage of the GI Bill to earn a master’s in clinical chemistry at the University of Oregon, where he worked through 1978, helping to train postdocs. He then taught for a year at the University of Oklahoma before moving back west to teach for twelve years at the University of Nevada in Reno, where he earned a doctorate in biochemistry.

Later, he worked at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, chairing its Clinical Laboratory Sciences program for seven years. In 1998, he became an associate professor at the Medical College of Virginia, in Richmond.

Mirroring his extensive civilian experiences, Wakayama wore multiple hats during his thirty-six-year military career. Trained as a medic, he also worked as a clinical laboratory officer, a biochemist, and a nuclear medical science officer. On the basis of his civilian jobs, education, annual Army evaluations, and military decorations and awards, he was elevated to the rank of colonel in July 1991.

Duty calls

In spring 2001, the Pentagon asked Wakayama to return to active duty, to help the government keep an eye on safety issues related to military equipment. His two-year, congressionally mandated position—working as a staff officer with the director of operational test and evaluation—was politically sensitive, reporting directly to defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Congress.

And it pitted Wakayama against military officials and defense contractors interested in getting new equipment adopted quickly, perhaps even when that meant leapfrogging over rigorous safety testing.

“Right away, I made enemies with the Army, the Air Force, the Marine Corps,” he says, laughing. “But I was a good choice because I was a reservist—I wasn’t looking for the next assignment or the next promotion—and I had the necessary research skills. The [defense] secretary always told me, ‘As long as you’re telling the truth, stick to your guns.’”

He did. He studied cabin pressure during high-altitude flying, suppressants used to douse engine fires, toxic fumes emitted by guns, chemical and biological decontamination methods, the ergonomics of confined spaces. At one point, Wakayama pushed to halt manned testing on an assault vehicle he thought presented safety concerns. Several defense contractors made it clear they weren’t happy with him. “But I didn’t budge,” he says. “So they finally stopped testing.

“It didn’t bother me to get criticized,” he adds. “I was just telling the truth. I’m a typical stubborn scientist. I’m open to suggestion, but just don’t lie to me.”

Wakayama’s Defense Department colleagues appreciated his approach, and his work ethic. Tom Carter remembers a research paper Wakayama wrote—in about a week—on safety issues related to the V-22 Osprey aircraft, which “really knocked my socks off,” Carter says. And Kirt Hardy, military assistant to the director of operational test and evaluation, says Wakayama’s six-month study of the assault vehicle he labeled unsafe had a crucial impact on its ultimate design.

Then came the events of September 11, 2001. That Tuesday morning, Wakayama was working in the Pentagon not far from where American Airlines Flight 77 hit, at 9:38. After he got outside and saw the wreckage, he went back into the burning building twice, leading and calling people out of the smoky darkness to safety.

In spite of warnings to leave the area (another hijacked airplane was still in the air—United Airlines Flight 93, which later crashed into a Pennsylvania field), Wakayama stayed on the scene until 9 that night, administering intravenous fluids to people who had been hurt, caring for those in shock.

After he got home, he spent hours more answering dozens of phone messages from worried family and friends. The next day—and every day thereafter for a week and a half—he returned to the Pentagon to help with the recovery and clean-up efforts.

The first day his staff returned to work, they gave him a standing ovation.

“I told them I wasn’t a hero,” Wakayama says. “I was just doing what I was trained to do. That’s my responsibility as a soldier.”

Nonetheless, the Army agreed with Wakayama’s colleagues. In December 2001, he was awarded the branch’s highest decoration for noncombatant valor, the Soldier’s Medal.

Last October, Northeastern honored Wakayama, too, presenting him with an Outstanding Alumni Award for his distinguished academic career, lifelong service to his country, heroism on September 11, and “selfless sharing” of his life story.

Though Wakayama downplays his own awards, he beams when telling how, in the late 1980s, he convinced a U.S. official in Japan to present his father with a medal commemorating the seventy-fifth anniversary of the end of World War I.

He was equally thrilled in 1988 when the U.S. government, after a nearly decade-long push by third-generation Japanese Americans, formally apologized for the Japanese internment. Seven years earlier, to support the lobbying effort, Kinzo Wakayama—who had always maintained the United States would redress its wrongs—came to America for the first time in nearly thirty-five years, to testify before a congressional committee.

It was a fitting resolution for an elderly, once-ignored activist. “He finally got to tell his story,” recalls his son. “At the end of the presentation, all the panel members thanked him.”

These days, Ed Wakayama has returned to academia, working in the Washington, D.C., office of the Georgia Tech Research Institute, where he conducts and manages research for the departments of Defense and Homeland Security.

He hopes one day to write his father’s story. In the meantime, as often as he can, he visits schools to talk about the Japanese internment. He makes sure his listeners hear about the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated Japanese American unit culled from the internees’ ranks (those who refused to serve were labeled draft dodgers and sent to jail). The 442nd became the most decorated unit of its size in the history of the U.S. Army.

And Wakayama freely criticizes the USA Patriot Act, passed by Congress just six weeks after the September 11 attacks. The legislation gave the government sweeping new powers to conduct surveillance on private individuals, access their medical and library records, tap their phones, monitor their web surfing, search their property, even detain them without charge—and do it all secretly, without a warrant or probable cause.

“The fifth and sixth amendments to the Constitution clearly indicate you cannot put someone in prison without due process of law,” the retired colonel told his Northeastern audience last fall. “We should enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, and we’ve got to know the nature and cause of the accusation.”

He added, “I want you to know what happened to the Japanese Americans, because it seems like it’s happening again today. My advice is, whatever the government does, question it.

“That’s your right.”

Copyright © 2004 Northeastern University Magazine All Rights Reserved

Karen Feldscher is a senior writer at Northeastern University Magazine. This story originally appeared in the March 2004 issue of Northeastern University Magazine.

![]()

[ The History Place Main Page | American Revolution | Abraham Lincoln | U.S. Civil War | Child Labor in America 1908-1912 | U.S. in World War II in the Pacific | John F. Kennedy Photo History | Vietnam War | First World War | The Rise of Hitler | Triumph of Hitler | Defeat of Hitler | Timeline of World War II in Europe | Holocaust Timeline | Photo of the Week | Speech of the Week | This Month in History ]

Terms of use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place.