The Molly Maguires: Hoax, Terrorists or Working-Class Heroes?

by Dr. James Ottavio Castagnera, Esq.

During the summer of 1968, when I was a rising senior at Franklin & Marshall College, the circus came to town. Specifically, Paramount Pictures filmed a movie called The Molly Maguires. The film starred Scottish superstar Sean Connery, aka, the first James Bond, and Richard Harris, also a hot Hollywood property. Most of the filming occurred at Eckley, Pennsylvania, a tiny mine-patch town in Lackawanna County to the north. Eckley, comprised of a single street, was owned by a single mine operator until it was acquired by the Commonwealth and incorporated into an anthracite-preservation project that includes mines and other artifacts of the near-dead industry that had once dominated and defined the region. It was tailor-made to be a movie set.

The only things Eckley lacked were a courthouse and a jail. Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, had both. In fact, my hometown boasted the selfsame courtroom and jail cells where four of the Molly Maguires had actually been tried and hanged in the late 1870s. Consequently, Paramount brought its Hollywood circus to Thorpe for two weeks -- two weeks in which I got to work as a traffic controller for the movie company, and got to drink beer alongside (well almost alongside) Connery and Harris in the saloon adjacent to the movie sets.

So who were the Molly Maguires? Let me start with a synopsis of the film, which came out in 1970. Richard Harris portrays James McParlan, a Pinkerton detective working undercover as Jamie McKenna, a small-time criminal hiding out in the Shenandoah mine patch. McParlan’s task is to infiltrate a secret society of Irish coal miners, led by Black Jack Kehoe (Connery), expose them and break them up.

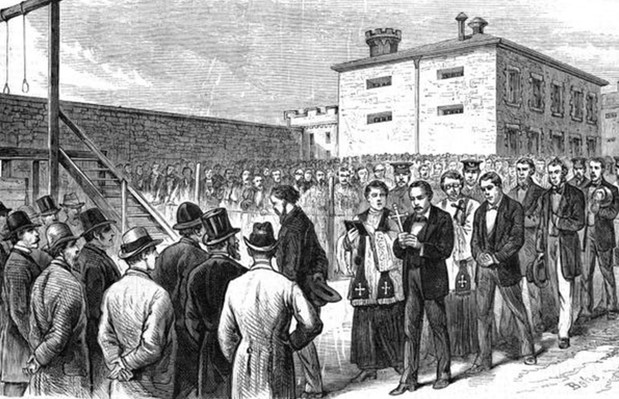

Connery depicts Kehoe as a militant coal miner, who leads a small band (about four) like-minded miners in a campaign of murder, arson and mayhem against the mine and railroad interests. The plot is painfully predictable: Kehoe and McKenna come to like and respect one another; McKenna becomes romantically entangled with the daughter of a lovable retiree whose health was ruined in the mine pits; faced with conflicted emotions, McKenna and McParlan engage in the tug of war for their single soul. In the end, ambition overcomes friendship and love. McParlan betrays Kehoe and his merry little band, testifies against them, and watches as they mount the gallows.

March to the Gallows The film, directed by the well-respected Martin Ritt, leaves a lot to be desired, particularly adherence to historical fact.

To begin, though John Kehoe had mined some coal in his time, he was a tavern owner, high official of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and small-time politician in Girardville, Schuylkill County, when he was indicted, arrested, tried and hanged as the so-called “King of the Molly Maguires.” His execution surprised him, since he had played an important role in winning the anthracite coal counties for the sitting governor. He expected a pardon and might have gotten one if Franklin Gowen, president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad hadn’t publicized the possibility -- this after having served as acting prosecutor in winning Kehoe’s conviction in the first place. (Kehoe did eventually win a pardon, 100 years too late, in 1979.)

Even the film’s fundamental premise -- the existence of a secret society called the Molly Maguires, tucked inside local lodges of the national benevolent Ancient Order of Hibernians has been sharply questioned since 20 “Mollies” were hanged in Carbon and Schuylkill Counties between 1877 and 1879. The “hoax” theory has it that Gowen and his capitalist colleagues, as well as the Democratic Party they controlled in Pennsylvania, were smarting from the rise of the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA), an early labor union, the so-called “Long Strike” led by the WBA in 1875, and the defeat of their Democratic gubernatorial candidate at about the same time. In league with Alan Pinkerton and his agency, Gowen and his minions conspired to insert an instigator into the Ancient Order of Hibernians. McParlan’s mission was never to unmask the Mollies. His task was to incite violence, incense the non-Irish populace of the coal region, and in the process, help smash the WBA and the Irish political machine before it could rival Tammany.

If this was the plan, Irish history was a helpful ally.

In Ireland’s west, where landlords’ oppression, periodic famine, and abortive uprisings were the hallmarks of Gaelic history, the secret society was woven into the fabric of resistance. Whiteboys, Ribbonmen, and, yes, Molly Maguires resisted evictions, cottage burnings and meted out erratic but oft times effective retribution. A turn toward such a secret vigilante organization in the no-less oppressive mine-patches of central-eastern Pennsylvania was too easily believable.

On the other hand, an ascendant Irish-American-led labor movement in league with gathering political strength posed a greater threat than any ragtag terrorists to the entrenched capitalist cabal that controlled the mines and rails of post-Civil War Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania.

And so the debate, partisan for the most part, continued down to the summer that Paramount came to Carbon and Lackawanna Counties, and still sputters sporadically to this day. What is beyond debate is the utter unfairness of the Molly Maguire trials. The fix, as they used to say, was in from the get-go. In an era when private counsel occasionally occupied the county prosecutor’s chair at trial, railroad and mine magnate Franklin Gowen led the successful prosecutions of the alleged Mollies. McParlan was an effective star witness, despite occasionally vigorous cross examinations by defense counsel. To wit:

Atty. L’Velle: “Did you directly assist in the crimes?”

McParlane (sic): I seemed to but it was not a fact that I did.”

L’Velle: “Did you or did you not? I want an answer.”

McParlane: “Of course I did not, so far as I was concerned; so far as the members are concerned, they thought so.”

L’Velle: “Then you were not the party that Jack Kehoe authorized to get the men to kill Bully Bill Thomas; were you or were you not?”

McParlane: “Certainly I was.”

L’Velle: “Did you deem that participation?”

McParlane: “No. I went down for the purpose of finding out what they are going to do."Not a juror was Irish in any of the trials. And not a juror questioned McParlan’s motives or his deeds. Not a defendant was acquitted. Still that doesn’t mean they weren’t guilty.

One defendant among the four hanged in the Carbon County Jail at the top end of Broadway in Mauch Chuck went to his death loudly screaming his innocence. I wrote a magazine story about this in 1973:

“Curse of Convicted Molly Still Lives”

by Jim CastagneraOn June 21, 1877 four men were hanged in the Central Pennsylvania coal town of Mauch Chunk. The four -- Michael Doyle, Edward Kelly, Alexander Campbell, and “Yellow Jack” Donohue -- were members of a secret society of Irish coal miners, known as the Molly Maguires. They had been convicted of murder in the most sensational trial to ever take place in the Carbon County courthouse, located in Mauch Chunk.

The Molly Maguires used terror and violence to combat the oppression of their English and Welsh foremen at a time when wages for a danger-filled day “in the hole” amounted to about fifty cents. The name was derived from a similar secret society, formed in mid-19th century Ireland, whose members frequently dressed in women’s clothing to better ambush the rent collectors. The power of the American Mollies peaked during the 1870s. They are credited with about 150 murders, and incited the mining communities to sporadic mob violence. They even organized strikes in unsuccessful attempts to bring the great mining and railroad companies to their knees.

Finally, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, hired by the mine owners, sent an undercover agent named James McParlen into the anthracite coal fields. He successfully infiltrated the Molly organization, and lived to testify at trials in Carbon and Schuylkill Counties which sent some dozen Mollies to the gallows.

“Yellow Jack” Donohue had been convicted of the 1871 murder of Morgan Powell, a foreman for the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company in Summit Hill, a tiny Carbon County community.

His three companions on the gallows had been found guilty of killing a mine foreman named John P. Jones.

Newspaper accounts of the executions record that “Yellow Jack,” Doyle and Kelly displayed no remorse as they faced the hangman’s noose. Only Campbell protested his innocence.

As they dragged him from his cell on the first floor of the county jail, Campbell flattened the palm of his left hand against the damp plaster wall.

“This hand print,” he vowed, “will remain here as proof of my innocence. He shouted this vow over and over as the sheriff’s deputies dragged him to the gibbet in the jail yard.

Campbell dropped two feet, six inches through the trap door. He took fourteen minutes to die. When the county coroner pronounced him dead at last, his body was cut down and taken home for burial.

The years passed. The Molly Maguires gave way to the United Mine Workers of America with its less violent tactics and more successful strikes. Alexander Campbell’s hand print remained.

After the turn of the century the palm print on the jail wall became something of a legend in the anthracite coal regions. Tourists from the Pennsylvania Pocono Mountains made the pilgrimage to Mauch Chunk to see for themselves the curious legacy left by Alexander Campbell.

The response of local law officers to this notoriety was less than enthusiastic. The open sore of Molly-Maguireism was slow to heal.

Anti-Irish sentiment persisted into the twentieth century.

In 1930 a Pennsylvania Dutchman named Biegler was elected sheriff in Carbon County. Biegler was known to be anti-Irish and anti-Catholic. He was determined to put an end to the legend which had grown up around the so-called ‘miracle’ in the first-floor cell.

One night he brought the county road gang into the jail and had them tear out the wall that bore the bizarre shadow of a human hand. When the rubble was cleared, the road gang put in a new wall and covered it with fresh plaster. Sheriff Biegler retired early the next morning, confident that he had obliterated the noxious Irish ‘miracle.’

When he awoke and visited the cell later that day, he was appalled to find that the fresh plaster was marred by the vague outline of a hand. By evening a black palm was clearly visible on the cell wall. Or so the story goes. Witnesses who will corroborate the strange incident are hard to find.

But a more recent attempt to obliterate the hand from the wall can be corroborated. In 1960 Sheriff Charles Neast took up residence in the jailhouse in Jim Thorpe. (The name Mauch Chunk was changed to Jim Thorpe in 1954 to honor the great Native American athlete.) To test the authenticity of the 83-year-old print, he covered it with a green latex paint.

As Ferdinand “Bull” Herman, the current jail turn-key, is pleased to point out to visitors, the shadow hand has once again reemerged and is clearly visible.

The Carbon County Jail, built in 1869, looks the same today as when it housed four condemned Irish terrorists nearly a century ago. In fact it was used by Paramount Pictures in 1968 for several scenes (including the inevitable gallows scene) in the movie titled The Molly Maguires.

The jail still has a few prisoners -- a duo of dope addicts and a local gent who wrote some bad checks -- but no prisoner has agreed to sleep in the cell containing the hand print. No cot is kept in the cell. The ponderous steel-grating door is opened only to accommodate tourists. According to “Bull” Herman the number of visitors to the cell grows each year.

“People come from all over to see the hand,” he says, “Had some folks in from Georgia not long ago. It seems people around here have begun to forget about it. But people from out of state hear about it somehow.”

No doubt the Paramount movie contributed to renewed interest in the Molly Maguires. Sadly, the film overlooked the hand print. But the legend of this eerie, black silhouette survives by word of mouth. “Bull” Herman is summoned to the massive, black and gold front doors of the jail by curious tourists more frequently every year.

It’s almost as if some power we know little about has decreed that the legacy of Alexander Campbell -- the hanged Molly who swore his innocence -- will remain to be seen by succeeding generations of Americans. And will remain to thrill and haunt the sons and daughters of the miners who used to dig the Black Gold.

In 1973 I hadn’t yet begun work toward my Ph.D. in American studies. I hadn’t yet researched the Mollies for a dissertation chapter. I hadn’t encountered the hoax theory. And, although my wife Joanne and I had left Roman Catholicism behind when we went off to college in 1965, I hadn’t considered the Church’s role in tarring Molly Maguires, Hibernians, and union organizers with the same broad brush.

The 1979 dissertation forced me to dig beneath the Hollywood version and, in sharp contrast to the script writers and the novelists, including Conan Doyle, conclude that a capitalist conspiracy might actually lie beneath the standard legend. By the time I had successfully defended the dissertation, the “hoax” theory had won me over.

Today, inevitably immersed in the morass of social-media-instigated conspiracies -- the Democrats stole the 2020 election; the Covid vaccines contain computer chips; the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol was an Antifa hoax -- I’m less open to conspiracy theories in general. And I find myself wondering if we do the men hanged as Molly Maguires a disservice in accepting the hoax theory. Black Jack Kehoe undoubtedly deserved his pardon, due to the obvious due-process violations polluting his trial.

But let’s remember that a pardon isn’t an exoneration; it brings with it an assumption of the recipient’s guilt. So perhaps, just perhaps, Sean Connery’s portrayal of Kehoe, albeit historically inaccurate in its surface details, comes closer to capturing the essence of the man than I once realized. And if we accept that Kehoe and at least some other “Molly Maguires” committed at least some of the felonies of which they were accused, we are left with a much tougher question, not a factual one, but a moral one: when is industrial injustice so severe that a violent response by oppressed workers is justified, if not by the law, then by a concept of “Justice” that surmounts an inadequate justice system?

Perhaps therein lies the real relevancy of the Molly Maguire story that resonates down the decades to our present day. Perhaps, just as the many conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination of Jack Kennedy distract from the meaning of the man as president, the hoax theory is a distraction from a reasoned consideration of how the Irish anthracite coal miners’ struggle for Justice (with a capital “J”) in the 19th century can help us think more deeply about the compelling parallels -- wealth disparity and worker exploitation -- in our own young century.

Picture Credit: Leslie’s Weekly (1877)

Jim Castagnera holds a JD and PhD (American Studies) from Case Western Reserve University. He is Of Counsel, Washington Int'l Business Counsel; Chief Consultant, Holland Media Services; Partner, Portum Group International. LLC. He is also the author of a young-adult novel, Ned McAdoo: Attorney at Large.

Copyright © 2023 Jim Castagnera All Rights Reserved

![]()

Return to The History Place - Personal Histories Index

The History Place Main Page

Terms of use: Private home/school non-commercial, non-Internet re-usage only is allowed of any text, graphics, photos, audio clips, other electronic files or materials from The History Place.